Marietta Horster, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz

As in most other cultures and communities, communication with the divine was an individual choice in the Roman world. For all public events, from political meetings and judgements to annual festivities in honour of a protective deity, the necessary prayers and rituals were organised and led by the elites.

The Roman magistrates and priests were responsible for ensuring the benevolence of the pantheon of gods, thereby guaranteeing the support and protection of the two main institutions, the Roman people and the senate (senatus populusque Romanus—SPQR). Thus, the welfare of the Roman state and all its inhabitants depended on the righteous and successful interaction between elected officials and the main deities.

The Latin term for all forms of address to the divine world was carmen. In official and semi-official contexts, prayers and hymns to the gods were formalised. Many of the prayers and invocations for support used in private contexts also contained such formal elements and were handed down through the generations. Which gods should be asked for help, when, why and, above all, how should they be asked? This was crucial for the safety of every individual and for the entire community.

For several hundred years, the Romans were successful, clearly supported by the gods! Whenever the gods granted their favour, they had to be thanked accordingly. The exact timing and manner had to be observed here, too, not only in public spaces but also in private family settings, such as when starting or finishing the day’s work, or giving thanks for a healthy newborn child or a good harvest: “Mars, father, I beseech and kindly ask you to be well disposed and favourable towards me, our house and our family.” (Cato, Agriculture 141. pp. 2–4, written in the mid-second c. BCE; for prayers see also R.M. Ogilvie, The Romans and Their Gods, 1969, pp. 24–40).

Some such invocations could have negative effects on people; magic and curses were also referred to as carmen due to their ritualised form (Ch. Guittard, Carmen et prophéties à Rome, 2007, pp.13–59).

Since the time of the Republic, various forms of human-divine communication, whether long hymns, short invocations or precise, rhythmically recited prayers by priests, have been referred to as carmen (sg.) or carmina (pl.). Referring to this process as ‘communication’ conveys the idea of a kind of religious commerce: first making requests and offerings (prayers, sacrifices and other devotional rites), then receiving favours from the gods and finally offering thanks (through sacrifices and other praising rites, including prayers). This interaction had melodious facets, perhaps even sweet, involving voices and instruments (M. Patzelt, Über das Beten der Römer, 2018, pp. 112–122). Even the songs of the birds and the sounds that can be produced by instruments were sometimes referred to as carmina (see TLL III col. 468–469 for examples). However, all such aspects come together in a festive, albeit less cheerful than solemn, set of concepts; by consequence, all kinds of versified texts or parts of texts with an emphasising rhythmic pattern could be later referred to as carmen.

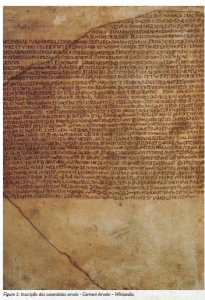

Before that, among the late Republican authors such as Cicero and Varro, the term carmen is predominantly found in religious or solemn public contexts, often in connection with priestly activities. This technical term was used to refer to any official invocation, including solemn formulas such as legal pronouncements made by officials (TLL III, 463–465). Th. Habinek (The World of the Roman Song, 2005) has emphasised the extraordinary stabilising function of such texts in society. The custom of referring to public presentations and written texts as carmina continued into the late antique period. The famous carmen saeculare, for example, was a festive poem thanking the gods and praising the Romans for persevering through good times and bad for 110 years, and for enabling so many successes. Other renowned prayers include the carmina of the Salii priesthood, the Fetiales and the Arval Brethren. “Help us, Lares (gods of the house and homeland). Do not let Marmar (Mars, the god of war) bring plague and ruin upon us” (CIL I2 2 = CLE 1; see Figure 1). This quotation forms part of a republican prayer inscribed in a report of its incantation in 218 CE. As in this case, most other solemn words and speeches that sound archaic are only known to us through later imperial texts. They probably attest to continuous usage and rites over centuries. Quintilian, a famous rhetorician from the Flavian period (69–96 CE) with excellent lexicographical training, informs his readers that he is unable to understand the words or meaning of the Salians’ prayers (Quint. Inst. Or. 1.6.40). However, Augustus, the princeps (first citizen of the state, 27 BCE–14 CE), proudly emphasises this very prayer in his accountability report (Res Gestae), which was published throughout the Roman Empire. The report states that the Senate had allowed his name to be included in the Salian prayer (nomen meum … inclusum est in Saliare carmen, RGDA 5, 10). From that point on, Augustus’ protection by the gods became a matter of state. One of the most tradition-steeped priestly groups would pray for him forever.

As with other members of the elite, the funeral ceremonies of Augustus were part of these highly ritualised events. On such occasions, the elogium referred to as a man’s merits, deeds, character and devotion to the state. In this context, the elogium could be considered a solemn carmen, which was publicly recited as part of rituals invoking the gods of the dead (Manes, Cic., Cato 61). Other than in the context of the elogium, the term carmen is rarely explicit in funerary contexts. One such exception is a senatorial decree from the time of Emperor Tiberius (14– 31 CE). For his deceased adopted son, Germanicus, the emperor should have the ‘carmen… [de laudando Germanico filio] suo proposuisset in aere incisum figeretur…’. “It was recommended that the ‘carmen’ honouring his son Germanicus should be carved in bronze” and erected in a public place (Tab. Siar., AE 1984, 408 of 19-20 CE). Furthermore, this text also announces that the Senate had decided to include Germanicus in the Salian priesthood’s prayers, just as they did with Augustus (see above).

This field of religious semantics does not disappear in many of the authors and publications from the Augustan period onwards. For example, in 17 BCE, the poet Horace was commissioned to compose the carmen saeculare (see above) during the reign of Augustus (see M.C.J. Putnam, Horace’s Carmen saeculare, 2000). According to the inscription in the senatorial report of the consuls, 27 girls and 27 boys performed this extraordinary event (CIL VI 32323). Alongside Virgil and Ovid, Horace was one of the three leading poets of the Augustan period. He also used the term carmen for his own verses, albeit with an ironic double-twist. As a (self-appointed) priest of the muse, he creates new and wonderful songs for both sexes (Hor. Od. 3,1). At the end of the book, the author says that the 30 odes are a kind of eternal monument and that he will be praised for introducing the special Aeolic-Greek poetic rhythm to the Italians (Hor. Od. 3, 30, 14: princeps Aeolium ad Italos deduxisse modos). However, Horace’s odes cannot be compared in terms of their virtuosity and diversity to the phenomenon that became increasingly popular in Italy and then in the provinces: the individual choice of inhabitants of the Roman Empire, with or without poetic talent, to compose or commission their (own or their loved ones’) epitaphs in verse. However, these people cannot be coined as the profane vulgus whom Horace seems to despise. Some epitaph authors invented new word combinations for such inscriptions; others were inspired by phrases from Horace or Virgil, borrowing entire or half verses from them or other poets.

Epitaphs often address the Manes, the divine spirits of the deceased, in the first line: Dis Manibus. However, despite such an invocation, these tomb inscriptions were not prayers. Following the address to the Manes are expressions of appreciation for the deceased, often of a very personal nature, dulcissimus—(the sweetest husband) and pientissima (the most faithful wife).

Unlike in Greek, where there are many, in Latin only a few prayers in verse by individuals from the imperial period have been carved in stone. These are specific requests and promises, beginning with an invocation of a god (e.g. ‘Hercule invicte’ – ‘invincible Hercules’, CLE 228 = CIL 6, 313, a versified prayer on an altar in Rome) and stating their purpose. Unlike an oral prayer, this monumentalised poetic form of addressing a god is connected to an object, often a gift such as an altar, sacrifice or statue, in fulfilment of a promise made to the deity. This promise would have been prompted by an initial prayer asking for protection, support, prosperity or safety.

The situation is different with Christian devotional texts in Latin, which are surprisingly more common than traditional ‘pagan’ ones. Priests and other prominent members of the Christian community chose this poetic form to make their words particularly impressive and memorable, both inside and outside of churches. In our CARMEN project, Eleonora Maiello, a doctoral candidate from Italy, focused on Christian religious poems inscribed in Italian churches from the fourth and fifth centuries. However, most of our early stage researchers (ESRs) have researched, or are still researching epitaphs from the imperial period, including Eleni Oikonomou from Greece. Funerary inscriptions account for approximately 80% of surviving Latin verse inscriptions on stone from the Roman period. Nevertheless, prose epitaphs are by far the most common, accounting for 80-90% of the total, with some variation between cities and regions. Apart from the CARMEN Innovative Training Network, the ERC- funded MAPPOLA project (Mapping out the Poetic Landscape(s) of the Roman Empire), led by Peter Kruschwitz from the University of Vienna (who is also a CARMEN member), focuses on questions such as “How is the empire’s considerable regional and ethnic diversity reflected in the engagement with inscribed verses?”

From its earliest attestation, the term carmen has conveyed a traditional, solemn and ritualistic, if not religious, connotation. Examining the historical development and diversity of its meanings is fascinating, especially considering that our tradition of referring to metrical inscriptions as ‘Carmina Epigraphica’ only emerged in the nineteenth century. Even though the term ‘carmen’ is now standard for all kinds of verse inscriptions and forms the acronym for our research group CARMEN, this says little about how the word was used in Latin in the Roman Empire. Antique inscribed poetry was multifaceted, but contrary to its modern label, it was rarely referred to as carmen.

Those interested in researching the use of Latin words in Roman times may find digital tools useful. Examples include the EDCS epigraphic database of Latin inscriptions and the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae lexicon. The first fascicle of TLL was published in 1900 and is now available online. Those researching the semantic shift from ‘prayer’ to ‘poem’ will find a lengthy, scholarly entry on the term carmen in TLL vol. 3 https://thesaurus.badw.de/tll-digital/tll-open-access.html.

Project summary

CARMEN explores Roman verse inscriptions as an important manifestation of communal art in Roman society. Our project helps to regain an eminent body of European folk art tradition. The reconceptualisation of this heritage emphasises the diversity of social and cultural performance in Roman antiquity. For further insights into the CARMEN project, see:

- Horster, Project Repository Journal, 17, 2023, 58-61. doi: 10.54050/PRJ1720281.

- Horster and S. Lefebvre, Project Repository Journal, 19, 2023, 24–27. doi: 10.54050/ PRJ1921178.

Nine of our early stage researchers have finished their PhD theses in 2024.

Project partners

Universidad del País Vasco (E), Université Bourgogne Europe (F), Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz (D), Sapienza Università di Roma (I), Universidad de Sevilla (E), Generaldirektion Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz (D), Universität Trier (D), Universität Wien (A) and project partners all over Europe.

Project lead profile

Since 2010, Marietta Horster has held the Chair of Ancient History at Mainz University. Her research focuses on the organisation of Greek and Roman cults, Roman imperial and late antique administration, organisation and prosopography, the transfer of knowledge, and the transmission of textual culture in the ancient world.

Project contacts

Prof. Dr Marietta Horster

JGU Mainz, Historisches Seminar Welderweg 18

55122 Mainz – Germany

Email: Carmen-itn@uni-mainz.de

Web: carmen-itn.eu

Funding disclaimer

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (MGA MSCA-IF) grant agreement no. 954689

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: Inscrição dos sacerdotes arvais – Carmen Arvale – Wikipedia.