Assistant Professor Edeltraud Aspöck, PhD, Department of Classics, University of Graz

The dead do not always ‘rest in peace’…

…cross-culturally, the reopening of graves has been documented in diverse ritual, religious, socio-political and mundane contexts. Interaction with human remains and objects in or from graves is not seen as taboo in many cultures, past and present, despite often being framed as such in archaeological interpretation.

The ERC PresentDead project investigates re-entries into inhumation graves of early medieval Central and Eastern European cemeteries, dating from the 5th to 8th centuries CE. Archaeological evidence from this period is dominated by cemeteries, sometimes with hundreds of graves, where the dead were buried in single graves, frequently along with an assortment of lavish objects, including weapons, ornaments, tools and pottery. These graves provide the main evidence for this period, as textual sources and remains of habitation are rare. Cemeteries and graves are used to infer information regarding many aspects of early medieval life, such as identities, social organisation, ideology, migration and mobility, and arts and crafts.

A large proportion of the graves show evidence of human intrusion that occurred while the cemeteries were still in use, often within only a few years or, at most, just decades after burial. Graves were reopened for a variety of reasons, including, for example, consecutive burial and the manipulation of human remains, but most frequently for the removal of grave goods. In these graves, the skeletal remains and artefacts were either found to be disordered, damaged or missing. Overall, the tendency has been, and often still is, to see such interferences as a hindrance to archaeological research and to interpret the removal of objects as materialistically motivated and unlawful plundering against the customs of that time. New research, however, has emphasised regularities in the practice, which has led to the hypothesis that the removal of artefacts could be part of practices related to the dead (Klevnäs et al., 2021).

Building on this research, the PresentDead project aims to investigate practical, conceptual and emotional dimensions of diverse human interactions with the materials of the dead in early medieval Central and Eastern Europe (from the 5th–8th centuries CE). Based on archaeological and written records, PresentDead sets out to identify and investigate all types of re-entries into inhumation graves and the other diverse types of engagements with the remains of the dead to understand the motivations and beliefs connected with these activities and their individual material substances. The analysis of post-burial activities in the archaeological evidence of graves and cemeteries and contemporary textual descriptions will provide different perspectives on the relationship between the living and the dead in the early medieval period. Overall, the PresentDead project contributes to our understanding of early medieval mortuary practices, the role of tombs, human remains, and objects from graves before and after burial.

Archaeology: investigating the spectrum of practices

When it comes to archaeological evidence, one of the major challenges faced by researchers is the poor documentation and preservation of archaeological data from graves that have been reopened. The records often lack detail, limiting our understanding of the reasons behind and the methods of grave reopening. In an innovative strategy to mitigate deficiencies of archaeological data, the PresentDead investigations range from high-resolution analyses, in which many details are collected (micro-archaeological excavations and reconstructions), to low-resolution approaches (integration of existing datasets and computational processing of previously published data). The detailed and high-resolution approaches inform all other types of investigations.

Central to the project is a methodological framework for bio-archaeology and field archaeology called ‘Archaeothanatology’, which has been developed in France over the last five decades (e.g. Duday, 2009). It pays particular attention to the formation of the archaeological record of a grave, which, in the case of an early medieval inhumation grave, develops from the burial of a freshly dressed corpse soon after death, usually in an organic container and possibly furnished with artefacts. Of these, we find in archaeological records of Central and Eastern Europe commonly only the non-organic remains such as the human skeleton or parts of it, as well as the non-perishable parts of objects the dead had been provided with. Based on a meticulous recording of the positioning of the individual bone elements and other finds, archaeothanatology aims to reconstruct the original layout of the grave as well as the formation of the archaeological record. The latter is subject to a complex interplay of natural factors, and, in the case of a reopened grave, there are also human activities upon the re-entry of the grave. The method will also be used to create a very detailed reconstruction of how the human remains (and artefacts) had been interacted with (Aspöck, 2018; Figure 2).

The micro-archaeology: creating high-resolution evidence

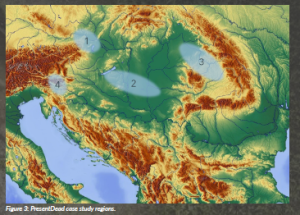

The PresentDead micro-archaeological excavations include, among other things: 3D single finds recording, including all bones in a ‘disturbed’ position; strategic soil sampling (disturbed and undisturbed samples); and wet sieving of the sediments. The detailed excavation data forms the basis for a whole range of scientific investigations and also for the 3D visualisation of the formation process of the graves. The digital models will be used to visualise and test different interpretations. In the first project year, we carried out an excavation campaign at the Avar-period cemetery of Achau, just south of Vienna, Austria (Özyurt et al., 2023; Aspöck, 2024; Figure 1).

Working on archival data in Austria, Hungary, Romania and Slovenia

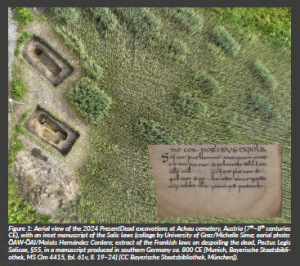

On a larger scale, the PresentDead project has started working on four case study regions in Central and Eastern Europe (Figure 3). Based on results from previous excavations of early medieval cemeteries, we will closely examine findings from graves that were re-entered and compare them with some that were left intact. The basis for analysis are our newly developed PresentDead research protocols for the analysis of human skeletons, artefacts and, of course, the excavation documentation.

- Danube Valley (Eastern Austria)

- Pannonian Plain (Hungary)

- Transylvanian Plateau and the North Pannonian Plain (Romania)

- South-eastern Alpine region (Austria & Slovenia)

Low-resolution analysis: data integration and (semi-) automatic classification of image data

The third part of the archaeological analysis involves computational processes. Our project database will be extended with existing data sets, and to analyse large numbers of graves quickly, we will train a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on good quality data to classify images of grave drawings according to the type of grave opening and disturbance. The aim is to get a large-scale view across regions, albeit with less information from individual graves.

Textual sources: reopening graves and engaging with corpses

The types of medieval texts in which grave disturbances are addressed vary widely, and the project will focus on close reading and comparative analysis of regulatory texts of Roman law, so-called ‘barbarian’ law codes as well as canon law collections, penitentials, etc., and historiographic texts, including historia [histories], chronicles, gesta [deeds, accounts], vitae [saint’s lives], etc. Critical editions of most of these texts have been published since the nineteenth century, many of which are now freely accessible online.

Synthesis

Through the interdisciplinary work of the project team, the synthesis and integration of the different perspectives on interventions in graves is an ongoing process throughout the duration of the project. Themes and questions arising from the material findings will influence the textual analysis and vice versa.

Furthermore, the complexity of the relationships between the information from the different types of sources will be digitally represented by innovative technical solutions through the semantic integration of the project data.

New approaches and expected impact

Reconstructing the range of human activities after burial in early medieval cemeteries will add a new layer of information to a field where graves ‘disturbed’ through post-burial activity are still seen as second-quality evidence. Bringing together historical and archaeological data has a long tradition in the research of the period, but frequently, archaeological evidence has been seen merely to ‘illustrate’ the written sources. This project will carefully integrate the different perspectives that material and textual evidence offer, taking into consideration anthropological models and knowledge that have had little impact so far. Moreover, in a highly innovative approach, the material and textual data will be semantically integrated, representing a novel way to analyse, reconstruct and visualise data for final synthesis.

Bibliography

Aspöck, E. (2024) ‘PresentDead blog post 5: PresentDead microarchaeological excavations season 1, Cemetery Achau, Lower Austria’, PresentDead blog. Available at: http://reopenedgraves.eu/presentdead-blog-post-5-presentdead-microarchaeological-excavations-season-1-cemetery-achau-lower-austria/ (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

Aspöck, E. (2018) ‘A high-resolution approach to the formation processes of a reopened Early Bronze Age inhumation grave in Austria: taphonomy of human remains’, Quaternary International, 474(B), pp. 131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.02.028.

Duday, H. (2009) The archaeology of the dead: lectures in archaeothanatology. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Klevnäs, A., Aspöck, E., Noterman, A.A., van Haperen, M.C. and Zintl, S. (2021) ‘Reopening graves in the early Middle Ages: from local practice to European phenomenon’, Antiquity, 95(382), pp. 1005–1026. Doi: 10.15184/aqy.2020.217.

Özyurt, J., Klostermann, P., Strang, S. and Tobias, B. (2023) ‘Nicht schon wieder ein awarenzeitliches Gräberfeld! Neue Erkenntnisse anhand interdisziplinärer Erforschung des neu entdeckten Gräberfelds von Achau’. In: Pieler, F. and Nowotny, E. (eds.) Beiträge zum Tag der Niederösterreichischen Landesarchäologie 2023. Veröffentlichungen aus den Landessammlungen Niederösterreich, 4. St. Pölten, pp. 26-33.

Project name

The PresentDead: Investigating Interactions with the Dead in Early Medieval Central and Eastern Europe from 5th to 8th Centuries CE

Project summary

The project aims to investigate the practical, conceptual and emotional dimensions of human interactions with the dead (graves, human remains and artefacts) in early medieval Central and Eastern Europe from the 5th to 8th centuries CE. Archaeological and textual evidence will be investigated through an innovative approach combining cutting-edge scientific methods, technical solutions and new theoretical approaches.

Project partners

The PresentDead project is based at the Department of Classics, University of Graz and at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University.

Project lead profile

Edeltraud Aspöck received a PhD in Archaeology at the University of Reading, UK (2009) and worked as a post-doc and as a junior research group leader (digital archaeology) at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. She is now Assistant Professor for Digital Archaeology at the Department of Classics, University of Graz. In 2023, she received the ERC Consolidator Grant PresentDead.

Project contacts

Assistant Professor Edeltraud Aspöck, PhD

Department of Classics

University of Graz, Universitätsplatz 3/II, 8010 Graz

Tel: +43 (0)316 380 – 2344

Email: edeltraud.aspoeck@uni-graz.at

Bluesky: @edeltraudaspoeck.bsky.social

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101089324.

Figure legends

Figure 1: Aerial view of the 2024 PresentDead excavations at Achau cemetery, Austria (7th–8th centuries CE), with an inset manuscript of the Salic laws (collage by University of Graz/Michelle Sima; aerial photo: ÖAW-ÖAI/Moisés Hernández Cordero; extract of the Frankish laws on despoiling the dead, Pactus Legis Salicae, §55, in a manuscript produced in southern Germany ca. 800 CE [Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Clm 4415, fol. 61v, ll. 19–24] [CC Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München]).

Figure 2: Analysis of movement of bone in an early Bronze Age inhumation grave at Weiden am See, Austria (Aspöck, 2018).

Figure 3: PresentDead case study regions.