The arid environment of Sudan and Nubia has preserved many archaeological remains of ancient clothing. These exceptional conditions enable the Fashioning Sudan project team to study ancient dress practices in their diversity, including questions related to materials, techniques, forms, gestures, body perspectives and sartorial traditions (Yvanez, 2023). A fundamental aspect of Sudanese dress practices is the importance of animal skin garments, either made of fur, hide or leather. This is particularly well documented in the earliest periods of Nubian history, especially on Bronze Age sites associated to A-Group, C-Group, Pan Grave and Kerma people (c. 3000–1500 BCE). More woven textiles appear with time, becoming prevalent during the first millennium BCE. Still, animal skins continued to play an important role in sartorial practices until recently.

Textiles and animal skins stem from very different chaînes opératoires, each of them complex and involving a long succession of sometimes difficult and time-consuming actions and knowledge (Andersson Strand, 2012; Veldmeijer and Skinner, 2019). This material is usually analysed by different experts, and rare are the studies that bridge the two material categories. Still, textiles and leather can both be recognised as tenets of the same “cloth culture” (Harris, 2012): they are flat sheets of flexible material and, as such, can fulfil similar functions around the body, such as providing warmth, protection and privacy. Ultimately, both materials were used by the same people and worn on the same bodies.

Textile and leather making are both dependent on animal husbandry and the exploitation of animals for fur, leather and wool. Within the team, we merge information from the two material categories to study ancient garments through transversal themes, using the same methods across materials. This short article will focus on a specific embroidery technique to highlight the relationships between textile and leather garments.

Material evidence

The starting point of this study is a specific embroidery pattern attested exclusively during the Meroitic period and its immediate aftermath (c. 100–450 CE). It consists of a circular motif made of tight stitches arranged in a spiral.

On textiles, this motif is made in chain stitches, created with a plied cotton yarn (s2Z) dyed in blue. It only appears on cotton garments, which can be identified as taking part in a specific ensemble: the loincloth and decorative apron outfit, exclusively made of cotton and seemingly reserved for special members of the male elite. The apron is usually decorated with a series of these embroidery circles, c. 2.5 cm in diameter, but the loincloth bears two larger ones, c. 5 cm in diameter, arranged at each upper corner of the piece. The spiral of stitches is tight, starting from the outside and closing in the centre of the circle, so as to form a roughly conical three-dimensional shape. Trials have shown that this motif can be easily produced by placing one’s finger on the reverse of the fabric and using it as a guide to form the spiral, with a slight upward pressure creating the conical shape on the front. It can be surrounded by an extra circle of chain stitches in another colour—a contrasting shade of blue or red—and is often finished with radiant small dashes in running stitches. On the aprons, the motif is usually disposed in a regular succession, at the end of horizontal lines made in stem stitches, or distributed in staggered rows.

Such examples are well attested in Nubia, on the settlement of Qasr Ibrim and in the cemeteries of Gebel Adda and Karanog (Wild, 2011; Yvanez, 2018). This type of embroidery is exclusively associated with cotton textile production, elite dress practices and a specific type of outfit, showing a high degree of technical and decorative standardisation.

A striking comparison to this textile embroidery motif was found on one exceptional leather object, discovered in cemetery 8-B-32.B on Sai Island. In its present form, the piece is composed of one folded leather item, forming a cylinder measuring 62 cm long and 14.7 cm wide. It was placed on the abdomen of the deceased, an adult male lying in a wooden coffin in tomb T11. While this individual was surrounded by other items, including elements of a leather quiver, this particular artefact (T11-97-12) was made of a very flexible and thin leather (c. 0.5 mm thick). The skin was dehaired and degrained, and thoroughly tanned, so no hair follicle holes are visible, giving the appearance and feel of nubuck leather. The item was made of several leather panels, sewn together into a large piece that is today agglomerated in many folds and much desiccated. Still, large portions of the artefact—if not all of it—were decorated in raised patterns of reddish colour, drawing volutes and lines in an intricate composition that is now very faded. More observation and analysis are unfortunately not possible, as the artefact was stored in the SFDAS’s magazine at the Sudan National Museum, plundered in the current war and still inaccessible. We hope this short notice can draw attention to the richness of Sudan’s heritage—there is much more information to be gained about little-known aspects of its rich material culture.

Besides the seams attaching panels together, a unique sewn decoration is visible on one side: a circular motif forming a small cone. The central part of the motif is made of a spiral of tight stem stitches, made with a thin leather thong. It is surrounded by a circular line of running stitches, made with a wider thong of red colour passing through longer incisions. The stitching draws the thin leather together, making folds around the embroidery. The circle was also placed at the end of a long line of stem stitches that acted as a seam between two panels, a position that indicates both the decorative and functional role of the embroidery.

Discussion

The two embroidery techniques, on textile and on leather, are dissimilar in both forms and material: the stitches are made of plant fibres and in chain stitches on the textile specimens, while a thin leather thong was employed on leather, in stem stitches. This can be simply explained by the fact that cotton fibres would not be strong enough to repeatedly go through leather, and because chain stitches would be more difficult to execute on leather. Indeed, embroidering leather necessitates planning the location of the stitching holes ahead of threading, so the holes can be pierced with an awl-type tool. In the case of chain stitches, the thread also needs to pass backwards through a loop, which would be very difficult to do smoothly with a leather thong. However, despite these different materials, processes and gestures, the final results are extremely similar: in both cases, the embroidered surface is fully covered, with the stitches going upwards towards the centre so as to form a little point, and of the same size.

The motif is very cohesive across the two media and can be identified as a floral pattern, the central circle being the main part of the flower, positioned at the end of a ‘stem’ made of stem stitches. The outer perimeter of contrasting colour and/or radiant stitches would then represent a corolla of petals, prompting their appellation as “sun-burst” flowers (Wild, 2011). In some isolated textile examples, the flowers are also flanked by two lines on both sides of the stem’s axis, finished by volutes, reminiscent of leaves.

We propose to interpret the visual and technical links between the two categories of artefact as signs of a cross-craft interaction between textile and leather production. Defined as “the contact between two or more crafts with adoptive and/or adaptive behaviours” (Brysbaert, 2007, p. 328), cross-craft interactions are particularly visible in the adoption of manufacturing techniques and decorative elements. In the textile world, they can result from shared workspaces, technology and visual expression (Ulanowska, 2018). These conditions seem to be met in our case. The examination of textile production areas has shown the use of common spaces, such as open courtyards, for a range of other ‘small crafts’, in which we can hypothetically place the sewing of leather objects (Spinazzi-Lucchesi and Yvanez, 2024, pp. 124–128). We have also demonstrated here that the embroideries belong to the same visual repertoire. In the last stages of their chaîne opératoire, textile and leather both become flat and flexible ‘cloth-like’ material, so their transformation into garments shares many technical aspects, especially in sewing.

Beyond their production, it is also important to state that the two categories of artefact share the same need: clothing. The folded and brittle condition of the leather piece precluded the understanding of the artefact as a whole. Still, comparisons with other leather garments, also made of sewn panels, indicate its probable use as a wrap either for the shoulders or, more probably, for the hips. Therefore, the garment could have been used as a skirt—placing the embroidery(ies) around the lower limbs—which is also the case for the textile loincloth and apron outfit. If the embroidered leather garment stands alone as the only preserved representative of its kind, the textile outfit is well-represented in the documentation and standardised. Interestingly, both leather and textile ensembles are associated with male individuals of high status, who can be linked to the practice of archery and sometimes military positions in the Meroitic hierarchy (Yvanez, 2018).

Therefore, by breaking down the barriers between material and related academic fields, we were able to identify cross-craft interactions through the tenuous evidence of embroidery, which, in turn, points to much wider socio-cultural codes. While we cannot interpret all the reasons behind them, we can recognise these codes as imbuing the specific dress practices developed by a very particular community within the ancient Nubian society.

References

Andersson Strand, E. (2012) ‘The Textile Chaîne Opératoire: Using a Multidisciplinary Approach to Textile Archaeology with a Focus on the Ancient Near East’, Paleorient, 38, pp. 21–40.

Brysbaert, A. (2007) ‘Cross-craft and cross-cultural interactions during the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Late Bronze Age’, in S. Antoniadou, A. Pace (eds.), Mediterranean Crossroads, Athens, pp. 325–359.

Harris, S. (2012) ‘From the Parochial to the Universal: Comparing Cloth Cultures in the Bronze Age’, European Journal of Archaeology, 15, pp.61–97. doi: 10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000006.

Spinazzi-Lucchesi, C. and Yvanez, E. (2024) ‘Textile Workshops in the Nile Valley? Questioning the Concepts and Sources’, in U. Mannering, M.-L. Nosch, and A. Drewsen (eds.), The Common Thread: Collected Essays in Honour of Eva Andersson Strand, New Approaches in Archaeology, 3. Turnhout, Brepols, pp. 117–132. doi: 10.1484/M.NAA-EB.5.138139.

Ulanowska, A. (2018) ‘Textiles in cross-craft interactions. Tracing the impact of textile technology on the Bronze Age Aegean art’, in B. Gediga, A. Grossman, and W. Piotrowski (eds.), Inspiracje i funkcje sztuki pradziejowej i wczesnośredniowiecznej, Biskupin – Wrocław, pp. 243–263.

Veldmeijer, A. and Skinner, L-A. (2019) ‘Nubian Leatherwork’, in Raue, D. (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Berlin, De gruyter, pp. 491–510.

Wild, F.C. (2011) ‘Fringes and aprons – Meroitic clothing : an update from Qasr Ibrim’, in De Moor, A. and Fluck, D. (eds.), Dress Accessories of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt, Lanoo, Tielt, pp. 110–119.

Yvanez, E. (2018) ‘Clothing the Elite? Patterns of Textile Production and Consumption in Ancient Sudan and Nubia’, Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, 31, pp. 81–92. doi: 10.23858/FAH31.2018.006.

Yvanez, E. (2023) ‘Archaeology of dress along the Middle Nile’, Project Repository Journal, 16, pp.12–15. Available at: https://www.europeandissemination.eu/article/archaeology-of-dress-along-the-middle-nile/19832. (Accessed: 01 Sep 2025).

Project summary

Fashioning Sudan is developing the archaeology of dress practices as a holistic method to reconstruct narratives of identity in ancient Sudan and Nubia. We investigate the remains of garments made from textile and animal skin, the artefacts that lie closest to our bodies from birth to death, and are at the crossroads between individuals, technology and social praxis.

Project partners

The project is hosted at the Centre for Textile Research, Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen. Activities are supported by the Section Française de la Direction des Antiquités du Soudan (SFDAS) in Cairo.

Project lead profile

Associate Professor Yvanez received her PhD in archaeology at the University of Lille III (France) before holding postdoctoral positions at the universities of Copenhagen and Warsaw. Her research focusses on the production and uses of textiles in the Nile Valley, with particular interests in the textile chaîne opératoire and its economy, dress practices and the use of textiles in burials.

Project contacts

Associate Professor Elsa Yvanez

Email: elsa.yvanez@hum.ku.dk

Web: www.fashioningsudan.ku.dk

Web: www.ctr.hum.ku.dk

Funding

This project has been funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101039416)

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

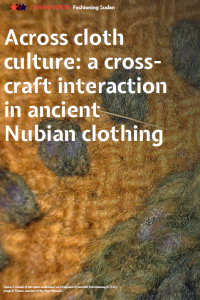

Figure 1: Details of the cotton embroidery on a fragment of loincloth from Karanog (E7511). Image E. Yvanez, courtesy of the Penn Museum.

Figure 2: Embroidered apron from Gebel Adda, ROM 973.24.3515. Image E. Yvanez, courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum.

Figure 3: Decorated leather garment from 8-B-32B, Sai Island. Image E. Yvanez/Sai Island Archaeological Mission.