Looking at Scandinavian Iron Age naming behaviour from the perspective of material culture.

Sofie Laurine Albris

Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion, University of Bergen and The National Museum of Denmark.

The ArcNames project, a Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellowship under Horizon 2020, took place at the University of Bergen in 2019–2021. Its main part was an analysis of the corpus of personal names in runic inscriptions from ca. AD 150 to 800. The names were related to material culture from the same period. The project also analysed the contexts wherein we find names and their use in place names.

The aim of the ArcNames project was to use the cross-disciplinary approach to shed new light on Iron Age concepts of identity. In other words, the project looked at how personal and social identities were articulated and perceived from various perspectives. This knowledge is relevant to further aspects such as gender, social status and the history of land ownership.

In this article, I will introduce some basic facts about Iron Age names in Scandinavia and summarise the results of the ArcNames project. The presentation follows some main themes central to our understanding of identity in pre-Christian Scandinavian society.

Names as meaningful entities

When someone was named in the Iron Age, the name was mostly formed of words from the ordinary vocabulary. This means that names were not mere sounds; they also encompassed a semantic meaning. Many names combined two words in seemingly random compositions, so-called ‘dithematic names’. Some scholars believe that meaning was irrelevant when these names were created. However, I discovered that the semantics of names correspond closely to central themes in other communication forms such as poetry, art and ritual. This means that names can be seen as media that worked within the general discourse and rhetoric of Iron Age society—and therefore, the semantic content should be seen as important.

Names as archaeological items

Runic writing first appeared in Scandinavia in the second century AD. Inscriptions are found on objects such as jewellery, weapons, tools and monuments of stone. Most inscriptions are brief, and names are often their primary or only content.

The purpose of writing names varies according to context and material. Weapons and tools with names mainly occur in large assemblies of battle equipment deposited in bogs, probably as sacrifices. Some of these inscriptions seem to have worked as makers’ or owners’ marks. Others may have been intended to consecrate the object or the fight. Jewellery with names is often found in fourth- and fifth-century female graves, yet the names are mostly male. The relation between the buried woman and the named man is unknown. It is thought that he may have crafted or commissioned the inscribed object.

In the fourth to seventh centuries, we see a rare phenomenon in Norway where stones inscribed with names are placed facing down near or inside a burial mound. Such depositions of names in funerary contexts tell us that writing names may have had ritual purposes. However, most inscriptions on stones are placed in highly visible positions and functioned as marks of power and status in the landscape. Both monuments and personal names used in place names were probably parts of strategies to claim family rights to land.

Names and kinship

In pre-Christian Scandinavian society, the family and kin formed the centre of most peoples’ lives. Your kinship and family relations determined your social position and possibilities in life. The emphasis on kinship in society is expressed in the importance of burial monuments. Older monuments were reused, and new ones were erected in the landscape. In Medieval Norwegian law, inherited land could be claimed by orally declaring your genealogy back to the burials in the mounds. Naming your ancestors in connection with concrete monuments in the landscape was likely also important in pre-Christian times. Claims to land were also a probable reason why personal names began appearing in Scandinavian place names from ca. AD 300. Thus, there is a close connection between names, kinship, land rights and monuments.

Kinship relations were also expressed through name choice. Scandinavian pre-Christian naming was a part of a Germanic tradition. Here, families could mark group belonging through alliterations with, for example, h-sounds or s-sounds. Further, names of new family members often combined elements from parents or grandparents. We only have few recordings of several names from within the same family. Yet, there are indications that some families favoured certain name elements. In a group of seventh-century rune stones from the Blekinge Region, Sweden, we meet three men: Hariwulfaz, Haþuwulfaz and Heruwulfaz, meaning respectively ‘army-wolf’, ‘battle-wolf’ and ‘sword-wolf’. Their names alliterate in h-sounds, and all contain the second Background photo: Landscape with burial element wulfaz, ‘wolf’ (Figure 1).

Names, animals and art

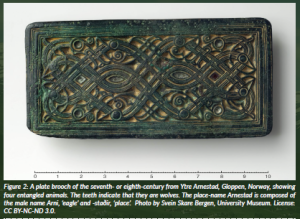

Animal symbolism was central to the pre-Christian Scandinavian world-view and plays a prominent role In Old Norse myths and legends. Both the gods and even some humans could change their appearance into various animals. The decorative styles of the Iron Age are called animal art because they are saturated with animal motifs, often in elaborate and deliberately elusive images (Figure 2). In some images, animals and humans blend or human faces or masks are composed from animal body parts (Figure 3).

The animals depicted in the visual art correspond closely with the species that are represented in names. In the ArcNames project, I have argued that this reflects how a common cultural language was used across various communication forms. In addition to the wolves mentioned above, we find words for bear, horse, wild boar, eagle, hawk, raven and snake. All these animals were associated with war and battle. Examples are Hrabnaz, ‘raven’ on the Swedish Järsberg rune stone and Eh(w)ō, ‘horse’ on a brooch from Donzdorf, Germany, both from the sixth century.

On an individual level, people possibly believed that an animal name attributed certain qualities to the name bearer. When a family favoured a certain animal, they may have identified with this animal as a group.

Ideal identities and gender

An examination of the semantic contents of all names known from Iron and early Viking Age runic inscriptions showed that the motifs in names could be divided into four main thematic categories:

- Warrior ideals and battle associations

- Battle, victory

- Weaponry: spear, sword, arrowshaft

- Battle related animals: wolf, raven, horse, hawk, bear

- Loudness and motion: roaring, moving fast, travelling far.

- Leadership and social responsibilities

- Ruling, rulership

- Sacral leadership (?) and performance

- Oathtaking

- Serving, guardianship/protection and hospitality

- Fame

- Advice, cunning, wisdom

- Theophoric names (words for and names of gods).

- Appearance and personal qualities

- Appearance particularly being dark of colour, having wild hair

- Love, being loved

- Gentleness, happy, cheerful

- Danger, malice, negative qualities

- “Not touched by sorcery”

- Being healthy, lucky, long lived (only Viking Age names)

- Other descriptive words (metaphors?).

- Group belonging

- Ethnic belonging or being a stranger

- Family and kinship

- Character of a place (of origin?).

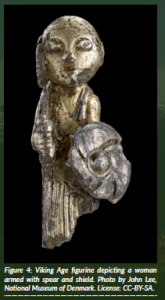

These themes reflect an ideology centred around the hospitable ruler and his warrior retinue. Interestingly, words related to battle and war are equally prominent in male and female personal names. Two word-elements were exclusively used as final elements in female names: Germanic *-gunþī and *-hilðī, Old Norse -gunnr and -hildr. These both mean ‘fight, battle’ and are common in continental Germanic and Viking Age female names as well as in modern names. The names indicate that ideals of character and abilities did not differ fundamentally between the sexes. Iconographic evidence from the Viking Age depicting armed females suggests that the connection between women and warfare had a strong symbolic value in this period (Figure 4).

Conclusion

A conclusion of the ArcNames project is that in Iron Age society, your name conveyed messages about kinship relations that could be deciphered by your contemporaries. Further, I believe that communicating the social identity encoded in your name was an important reason for writing names on objects and monuments.

When we meet new people, the first thing we learn about them is often their name. Archaeologists studying people of the past learn intimate details about their way of life, homes, travels, diets or illnesses. Yet, we rarely know what they were called. Studying names of the past allows its people to step out of anonymity and for us to get to know them better.

Image legends

Figure 1: The Istaby Rune stone from Blekinge, Sweden reads: In memory of Hariwulfʀ, Haþuwulafʀ, descendant of Heruwulfʀ, wrote these runes. Photo by Bengt A. Lundberg, Riksantikvarieämbetet. License: CC-BY 2.5.

Figure 2: A plate brooch of the seventh- or eighth-century from Ytre Arnestad, Gloppen, Norway, showing four entangled animals. The teeth indicate that they are wolves. The place-name Arnestad is composed of the male name Arni, ‘eagle’ and -staðir, ‘place’. Photo by Svein Skare Bergen, University Museum. License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 3: A brooch of the seventh- or eighth-century with bird/mask motif. A metal detector find from Jutland, Denmark. Photo by the finder, Geoffrey de Visscher, with kind permission.

Figure 4: Viking Age figurine depicting a woman armed with spear and shield. Photo by John Lee, National Museum of Denmark. License: CC-BY-SA.

Article summary

Project name

ArcNames

Project summary

ArcNames investigated naming in Iron and Viking Age Scandinavia from a material culture perspective. It aimed to understand the role of names in identity constructions and as markers of status and landholding in place names and runic monuments.

The vocabulary in personal names corresponded with iconographic and poetic motifs, and names conveyed messages about status, kinship, affiliations and personal qualities.

Project lead

Sofie Laurine Albris has an archaeology degree from the University of Copenhagen (UCPH) and a PhD combining archaeology and toponymy, completed at the Danish National Museum/ the Department of Nordic Research, UCPH. Her research investigates Iron Age social and religious life in the landscape and on the individual level. She further has experience with excavations, university teaching and public dissemination.

Project partners

The project was conducted at the Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion at the University of Bergen, Norway, in cooperation with professor in archaeology Randi Barndon.

Contact details

Sofie Laurine Albris

National Museum of Denmark

Frederiksholms Kanal 12

1220 Copenhagen Denmark.

Email: sofie.l.albris@uib.no or laurine.albris@natmus.dk

Facebook: ArcNames

Website: https://arcnames.w.uib.no/

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (MGA MSCA-IF) grant agreement No. 797386.