In modern science, the frontier between pure discovery and technology is a blurred, fertile ground where pure curiosity meets applications. E-Nucl resides in this liminal space, where insights from fundamental physics can reshape the design rules of next-generation microtechnologies.

At the heart of this story lie technologies that exploit phase transitions in fluids, yet are penalised by our poor understanding of the very beginning of phase change, which determines how the transformation actually starts.

A compelling example is the heat management of the ever-increasing miniaturisation of high-power electronics. As devices shrink and densify—today’s chips host tens of billions of transistors—they dissipate unprecedented heat fluxes (tens of MW/m² comparable with the flux on the sun’s surface). Thermal management is, nowadays, the bottleneck that threatens progress, from hyperscale data centres to radiation-hard space avionics.

For these systems, traditional cooling strategies are reaching their limits. Among different approaches, one of the most promising routes is two-phase cooling, which leverages the latent heat absorbed and released in boiling and condensation. The potential of this technique can be grasped by comparing the typical energy required to heat up 1 gram of water and the same amount required to evaporate it.

As a bare estimate, heating 1g of water from 25 °C to 100 °C requires ≃314 J, whereas its isothermal vaporisation requires ≃2157 J.

Beyond cooling, a predictive theory of onset extends far past microelectronics: it underpins cryogenic propellant management and thermal control in space, enables reliable microfluidic and soft-robotic actuation by timing/ locating nucleation, boosts water and environmental technologies via accurate droplet-formation maps and improves manufacturing and health (semiconductors, directed self-assembly, pharmaceutical crystallisation) by controlling the very first steps that set outcome distributions.

The development of two-phase technologies is hamstrung by a simple, stubborn question we still cannot answer predictively: when and how does a new phase emerge in a fluid?

This is the problem of nucleation—the formation of rare, critical bubbles or droplets that trigger the liquid–vapour transition (and, more broadly, the first-order phase changes). Despite more than a century of theory and experiments, our understanding of incipient phase change remains fragmented. The puzzling measurements of ‘boiling points’ of superheated fluids or ‘cavitation pressures’ of stretched liquids are a perfect example of that. Classical models are equilibrium-based or heavily empirical, and no available tool can, with confidence, tell an engineer when a superheated microchannel will boil, how many bubbles will appear, how fast they will grow, or what acoustic signature they will emit.

Why nucleation is so difficult to predict

Why is this so hard to characterise? Because nucleation is rare, multiscale and out of equilibrium.

Molecules jiggle on a temporal scale of trillionths of a second, but the waiting time to the first critical nucleus in a micrometric device may vary from microseconds to minutes—twelve orders of magnitude apart. Critical nuclei are nanometric, while engineered geometries span from a couple of microns to millimetres; four to five orders of magnitude in space.

In summary, while it is well recognised that the problem is multiscale in space, it is perhaps less appreciated that it is equally—if not more—multiscale in time, with dynamics spanning many decades. Compounding this, practical settings are almost invariably out of equilibrium, which further complicates theoretical analysis and model validation. As a matter of fact, realistic settings feature temperature gradients, flows and pressure waves, so the system is not at equilibrium—the regime where most traditional tools are at their best.

Despite occurring at nanometric scales, stochastic nucleation events initiate the actual phase transformation and set the course of the ensuing macroscopic fluid dynamics. In short, nucleation is a sort of ‘black-swan event’: almost nothing happens—until it does—and that single event dictates the macroscopic outcome.

E-Nucl’s new approach

To date, classical approaches address this problem, focusing on two different scales: macroscopic with continuum mechanics, and microscopic with atomistic description.

Continuum multiphase hydrodynamics (Navier–Stokes with interface physics) comes into play once bubbles or droplets exist, but they handle the onset with empirical triggers or oversimplified criteria. Molecular dynamics resolves atomistic detail, yet cannot bridge the huge time/length gaps to predict device-level statistics. Even sophisticated equilibrium techniques (free-energy-based calculations) struggle once heating ramps, flows and inertia matter.

The result is an uncomfortable regime where industrial design reverts to trial-and-error heuristics—effective in the short term, but ultimately fragile.

Addressing this question requires a deliberate blending between communities. Thermal science and, more broadly, process engineering must interface with theoretical physics. The former brings device constraints, materials and diagnostics; the latter addresses metastability and fluctuations, irreversibility and scale bridging from atoms to continuum fields.

E-Nucl is designed as that interface: a project where engineering questions are declinated in modern physical terms and answered with models that remain faithful to the underlying physics while being usable in practice.

Pursuing this objective, E-Nucl proposes a different path. Instead of treating nucleation as either a fully atomistic or a fully macroscopic phenomenon, it embraces the mesoscale, where fluctuations are strong, interfaces are thin but resolvable, and hydrodynamics can still be described by field equations.

The project develops a stochastic, physically-based framework that links microscopic fluctuations to macroscopic fluid motion. The idea is basically simple: if phase change is triggered by rare fluctuations and shaped by fluid motion, then both must appear explicitly in the description.

E-Nucl, therefore, integrates several pillars:

- Fluctuations are not a nuisance; they are the drivers of onset. The framework treats them with statistical mechanics and quantifies their role in forming critical embryos.

- Hydrodynamics is not an afterthought. Compressibility, wave emission, viscous dissipation and inertia are included, so the onset and the immediate aftermath are connected rather than siloed.

- Real-fluid thermodynamics matters. Surface tension and its curvature dependence, metastability and equations of state are brought in so that predictions reflect actual materials, not idealised fluids.

- HPC (high-performance computing) makes the difference; we exploit modern computational power to perform simulations involving billions of degrees of freedom for a ‘hydrodynamical-ab-initio’ description of phase change in fluids.

With these ingredients, E-Nucl aims to replace ‘rules of thumb’ with reliable, experiment-facing predictions for onset and early evolution—exactly the information designers need before building hardware—laying the groundwork for a computer-aided engineering of phase change. Success means knowing—under your specific design scenario—when onset will occur; how many nuclei will form and where (defects, microcavities, or bulk); how they evolve in the first instants; and which levers (wettability, surface patterning, fluid choice) will influence both onset and early dynamics. E-Nucl’s deliverables are tailored to answer those questions.

Project objectives: from theory to application

To make this vision operational, E-Nucl is organised around two linked objectives.

Objective 1: A time-resolved, multiscale picture of nucleation in fluids

By combining fluctuating hydrodynamics, the thermodynamics of multiphase systems, and large deviation theory, we will build a high-fidelity, space–time picture of how critical bubbles and droplets emerge in realistic environments—quantifying which hydrodynamic fields appear first, whether inertial effects bias the pathway, and how surface chemistry and the fluid’s chemical composition guide or suppress onset.

Objective 2: HPC tools for in-silico trials of archetypal microtechnologies

We exploit the theoretical framework from Objective 1 to deliver HPC, GPU-accelerated codes for in-silico trials that inform the conception and design of future microtechnology. These tools couple the new physics with HPC to run predictive simulations on realistic systems, bridging theory and engineering practice.

E-Nucl is not just about better chips or faster micro-actuators. It asks—and sets out to answer—a fundamental question: how does a new phase emerge from a fluctuating fluid? By resolving the incipit of phase change and its spatiotemporal behaviour, the project aims to restore predictability where it has long been missing. That means fewer guesses, fewer costly prototypes, and more principled innovation across technologies that touch energy, information, health and the environment while progressing fundamental science in fluid mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical physics.

Project summary

E-Nucl proposes a paradigm shift in the continuum modelling of phase transitions in fluids, combining large deviation theory with multiphase fluctuating hydrodynamics. This new framework could represent a turning point in fluid dynamics, bridging the gap between atomistic mechanics and macroscopic hydrodynamics, and paving the way for the first in-silico, high-fidelity experiments of phase change-based microtechnologies.

Project partners

E-Nucl is based at the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering of Sapienza University of Rome.

Project lead profile

As of 2025, Mirko Gallo is Associate Professor of Fluid Mechanics at Sapienza University of Rome and a Junior Fellow of the Sapienza School of Advanced Studies. Previously, from 2023 to 2025, he served as Researcher at Sapienza. He earned his PhD in Theoretical and Applied Mechanics from Sapienza in 2019 and held postdoctoral appointments at DIMA (fluid dynamics) and at the University of Brighton (computational physics). His research focuses on mesoscale modelling of fluids, integrating fluid mechanics, statistical mechanics, applied mathematics, HPC and soft-matter physics for multiscale studies. He received the AIMETA Junior Prize for fluid mechanics (2022) and an ERC Starting Grant (2024).

Project contacts

Mirko Gallo, Principal Investigator

Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Via Eudossiana 18, Rome, IT 00184

Email: mirko.gallo@uniroma1.it

Web: https://sites.google.com/uniroma1.it/liminal

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101163330).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

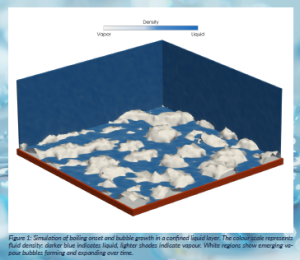

Figure 1: Simulation of boiling onset and bubble growth in a confined liquid layer. The colour scale represents fluid density: darker blue indicates liquid, lighter shades indicate vapour. White regions show emerging vapour bubbles forming and expanding over time.