Prof. Diego Misseroni and the S-FOAM team, Università degli Studi di Trento

How origami is shaping the future of materials, structures and machines

Origami-inspired structures, in particular Kresling and trapezoid-based patterns, can be engineered to display programmable mechanical behaviours. This is achieved through the integration of mathematical modelling, experimental investigations and a range of manufacturing methods such as laser cutting, milling and 3D printing.

In this way, the influence of crease geometry, material properties and folding sequences on deformation modes and energy landscapes can be revealed. The resulting insights enable the design of adaptive, foldable systems with applications in robotics, materials science and mechanical computing.

What if folding could do more than create art? What if it could shape machines, program materials and unlock new technologies?

In recent years, origami has moved far beyond its traditional roots. Folding is no longer confined to artistic expression but is increasingly recognised as a powerful engineering tool. When a flat sheet is patterned with precise creases, it can expand, contract, twist or store energy without the need for motors, hinges or screws. By understanding these mechanisms, it becomes possible to design structures that are lighter, smarter and more adaptable than conventional alternatives.

Drawing on the principles of folding, research now integrates theoretical modelling, advanced materials and modern manufacturing methods. Analytical models, controlled experiments and 3D-printed prototypes are combined to create foldable structures that respond predictably and purposefully, performing exactly as designed.

From folding paper to precise design: understanding the mechanics of Kresling origami

The Kresling pattern may appear simple at first glance, consisting of folded triangles arranged around a cylinder, yet its behaviour is highly intricate. It does not merely collapse or twist. Instead, it couples axial motion and rotation, producing both in a single continuous movement.

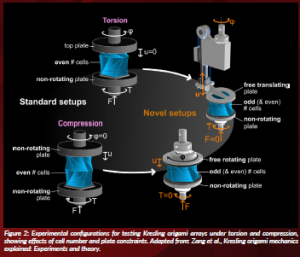

This behaviour has been described through an enhanced 5-parameter analytical model, where geometric parameters are incorporated into an energy-based framework to predict responses under combined compression and twisting. Special experimental setups were developed to test these predictions. These enabled the study of both individual Kresling cells and larger arrays without imposing restrictions on chirality or symmetry. The experiments revealed a direct link between folding pathways and the underlying energy landscape.

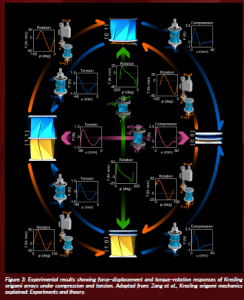

A key result is that the folding pathway can be controlled simply by varying the loading applied at the ends of the array. Even when cells are arranged with random chirality, this approach generates multiple programmable folding routes, each corresponding to a distinct structural configuration. In this way, compression and twisting direction guide the system toward predictable outcomes without constraining the arrangement of the cells themselves.

Tests on two-cell arrays further clarified these mechanisms. When both cells share the same chirality but have different energy barriers, only a single folding path emerges, regardless of loading condition. In contrast, when the cells have opposite chirality, several distinct folding paths become available. These can be selected by applying different loading conditions, such as clockwise or counterclockwise twisting. The interplay between energy barriers and chirality thus provides an effective means to control folding behaviour and to program the final configuration.

Overall, these findings show that mechanical logic can be embedded directly within the origami structure. Rather than relying on external controllers, the system governs its own behaviour. This principle opens pathways toward reconfigurable mechanisms and mechanically encoded computation, in which folding patterns serve not only as functional elements but also as units of memory (Zang et al., 2024).

Unfolding geometry: trapezoid-based origami as responsive metamaterials

While Kresling cells highlight the role of cylindrical symmetry and chirality, it is also important to ask what happens when familiar crease patterns are left behind. Traditional origami tessellations often rely on parallelogram faces, which place inherent limits on how surfaces can deform. By relaxing these constraints, new opportunities arise.

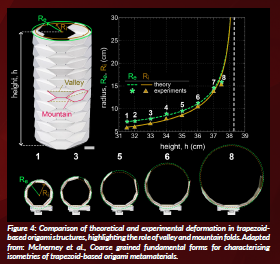

To investigate this idea, attention was directed to crease patterns built from trapezoidal faces, referred to as trapezoid-based origami (TBO). In contrast to standard patterns, TBO structures display rich and large-scale behaviour that is governed by small local folds. A continuum model was developed to connect discrete folding actions with smooth deformations, mapping the motion of rigid panels to global strain and curvature of the folded surface.

This framework revealed two principal deformation modes. The first is a breathing mode, in which the structure uniformly expands or contracts. The second is a shearing mode, which permits lateral shifts. These modes can be identified and described using the fundamental forms of the folded surface, which serve as the mathematical descriptors of shape.

A representative specimen, known as Arc-Morph, was fabricated and tested. The experiments confirmed the predictions of the model. Depending on the configuration of folds and angles, the structure could bulge, narrow or follow complex non-monotonic deformation paths.

These findings provide a way to classify origami geometries according to function rather than appearance. They also make it possible to constrain the design space in inverse design processes, focusing only on crease types that enable the desired deformation. For engineering applications, this means origami can operate as a true mechanical metamaterial, where the behaviour of the surface is defined by geometry rather than by the base material itself (McInerney et al., 2025).

Folding in the future: 3D printing and programmable energy landscapes

No origami design is complete unless it can be realised physically. A third line of research is therefore focused on the use of 3D printing to translate origami mechanics into practical and manufacturable structures, with particular attention to a Kresling cell.

The main challenge lies in the creases. In practice, creases are neither infinitely thin nor perfectly elastic. When produced in rubber-like or photopolymeric materials, they introduce effects such as viscoelasticity and material relaxation, both of which influence how energy is stored and released during folding.

A systematic variation of the crease cross-section geometry, in particular the internal thickness, made it possible to achieve and tune bistability. Reducing crease thickness by more than 50% proved especially effective, enabling reliable switching between stable configurations even in viscoelastic materials.

A monomaterial approach was also developed by introducing voids that act as perforated creases. This strategy allowed stiffness to be tailored within a Kresling cell fabricated from a single printed material, while still enabling bistability and controlled energy storage. Photopolymers with intermediate stiffness, approximately 600 MPa, were identified as optimal for achieving this behaviour and may also support future implementations at the micro-scale.

Bistability was further observed across different timescales, even in soft materials, showing that energy storage and release can be designed by controlling the geometry of the creases. Crease design, therefore, emerged as a critical tuning parameter, influencing not only motion but also temporal response and energy control (Mora, Pugno and Misseroni, 2025).

A unified vision: designing the folded machines of tomorrow

Across these studies, a unifying principle emerges. In origami-inspired structures, the arrangement of folds, their sequence and the material properties together determine how the system moves, responds and adapts.

From Kresling cells and trapezoid tessellations that deform through expansion, contraction and twisting while storing energy, to three-dimensional printed creases that control energy landscapes on demand, origami is not only shaping new forms. It is giving rise to a new design language in engineering. These insights make it possible to envision deployable systems that change shape on cue without motors or complex hinges, wearable devices that flex and conform with movement, impact-absorbing materials with tailored stiffness zones, and robots constructed entirely from patterned folds that react not through code but through geometry.

The power of origami lies not only in its elegance but also in its ability to bridge computational-aided design and physical worlds. Fold by fold, systems are being created to compute, adapt and perform, with their behaviour encoded entirely in their geometry.

References

McInerney, J.P., Misseroni, D., Rocklin, D.Z., Paulino, G.H. and Mao, X. (2025) ‘Coarse-grained fundamental forms for characterizing isometries of trapezoid-based origami metamaterials’, Nature Communications, 16(1), 1823. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-57089-x.

Mora, S., Pugno, N.M. and Misseroni, D. (2025) ‘Programming the energy landscape of 3D-printed Kresling origami via crease geometry and viscosity’, Extreme Mechanics Letters, 77, 102314. doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2025.102314.

Zang, S., Misseroni, D., Zhao, T. and Paulino, G.H. (2024) ‘Kresling origami mechanics explained: experiments and theory’, Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 188, 105630. doi: 10.1016/j.jmps.2024.105630.

Project lead profile

Diego Misseroni is a Professor of Space Structures at the University of Trento, Italy. He obtained his PhD in ‘Structural and Solid Mechanics’ from the University of Trento in 2013. In 2014, he was a Marie Curie experienced researcher at the University of Liverpool, UK. In 2023, he was a Fulbright visiting scientist at the School of Engineering and Applied Science, Princeton University. Dr Misseroni has received several awards, including the 2025 Huajian Gao (SES) Young Investigator Medal, 2024 Thomas J.R. Hughes (ASME) Young Investigator Award, an ERC Consolidator Grant, the 2022 Extreme Mechanics Letter (EML) Young Investigator Award, a Fulbright fellowship, the 2022 Zwick Roell Science Award, the Paul Roell Medal and the 2017 AIMETA Junior Prize. His extensive research interests span the mechanics of solids, materials and structures, encompassing architected materials, metamaterials and origami engineering. Additionally, he delves into flexible structures, buckling phenomena and instabilities of structures undergoing large deformations.

Team

Anandaroop Lahiri is a postdoctoral fellow with a PhD in Solid Mechanics from the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. His research specialises in origami-inspired metamaterials.

Guozhan Xia is a postdoctoral fellow with a PhD in Solid Mechanics from Zhejiang University. He also completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Southern University. His expertise includes nonlinear analysis, instability in soft electroactive plates and advanced metamaterial behaviour.

Sveva Juliano is a PhD student who earned her M.S. from Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II. Her research focuses on the homogenisation of origami metamaterials.

Shuhong Wang is a PhD student who earned his M.S. from Chongqing University. His research focuses on designing multistable metamaterials inspired by origami principles.

Arman Toofani is a PhD student who earned his M.S. from Guilan University. His research focuses on bio-inspired origami structures.

Joao Pedro Norenberg is a visiting PhD student from São Paulo State University. His research focuses on metamaterials inspired by origami principles for energy harvesting.

Acknowledgements

The S-FOAM team gratefully acknowledges the valuable collaboration of our colleagues at Princeton University (Prof. Glaucio H. Paulino, Dr Shixi Zang, Dr Tuo Zhao), the University of Michigan (Prof. Xiaoming Mao, Dr James McInerney), and the Georgia Institute of Technology (Prof. Zeb Rocklin), whose contributions were essential to this research.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101086644.

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: Research design overview showing how crease geometry and material viscosity influence bistability and energy landscapes in Kresling origami structures. Adapted from: Mora et al., Programming the energy landscape of 3D-printed Kresling origami via crease geometry and viscosity.

Figure 2: Experimental configurations for testing Kresling origami arrays under torsion and compression, showing effects of cell number and plate constraints. Adapted from: Zang et al., Kresling origami mechanics explained: Experiments and theory.

Figure 3: Experimental results showing force–displacement and torque–rotation responses of Kresling origami arrays under compression and tension. Adapted from: Zang et al., Kresling origami mechanics explained: Experiments and theory.

Figure 4: Comparison of theoretical and experimental deformation in trapezoid-based origami structures, highlighting the role of valley and mountain folds. Adapted from: McInerney et al., Coarse grained fundamental forms for characterising isometries of trapezoid-based origami metamaterials.