The journey from MSCA project to ERC proposal

This article is not concerned with a single project but seeks to outline a process. I recently conducted a research project on angels from which a promising concept emerged. It is centred on the notion of personification, i.e. representing abstract ideas under the aspect of human shape. Although the two projects are related, each has its own logic. They also have different wingspans.

The angel project was designed to fit a circumscribed topic focusing on a relevant yet limited timeframe (fifth to sixth century CE) and geography (Egypt, Syria, Palestine). The personification proposal we intend is more ambitious. The subject concerns numerous domains: art, literature, philosophy/theology but also, on a broader scale, the perception of the self and one’s relation with others. The way human form embodies various expressions of the mind is the key feature to approach the transformation of society and civilisation in a global perspective from Antiquity to Byzantium and Western Middle Ages. Such a project needs a team. To achieve breakthrough results, one would expand the methodology and the experience gained with the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions project to the new European Research Council proposal.

Angelic achievements

The ALATA project—The Making of Angels in Late Antiquity: Theology and Aesthetics—took place at Sorbonne University (2018–2020). The Project Repository Journal published an overview of it in a previous issue (Lauritzen, 2020a). In the meantime, more linked publications have appeared (Lauritzen, 2020b).

The project conference was held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, the proceedings will soon be published, counting more than 35 articles ranging from the Jewish origins of Christian angels to the modern Yezidi religion (Lauritzen, 2021). Also, I am currently writing a scholarly book on the aesthetics of angels in Late Antiquity (Lauritzen, 2022a [forthcoming]). This tackles the question of the legitimacy of representing the divine by means of images.

Angels are a borderline case. On the one hand, they are not supposed to be visible, as they do not have a material body, but on the other hand, they are present everywhere in Christian art.

Personification developments

But how to pass from angels to personifications? The greatest theological innovation of Christianity is the Incarnation. If God assumed a human body in the person of Christ, representing the invisible becomes possible. However, the human mind, in its weakness, cannot contemplate the divine splendour as such. Mankind needs visual support to try and understand it. Angels are spiritual beings, and therefore they do not have a body. Yet, artists gave them a human appearance like the one of Christ. Other invisible entities had long been represented with a body since Antiquity. Psyche, for instance, “Soul” in Greek. On a second-century CE mosaic from Antioch, one might easily mistake the white-clothed, white-winged Psyche for an angel, save the context that does not allow the confusion to happen (Figure 1).

Gender and clothes

Two characteristics are here intertwined: gender and non-nudity. Angels are gendered as masculine (albeit non-virile), and personifications are predominantly feminine (with no reference to generation). In classical art, nudity was not an issue. In Christian art, however, both angels and personifications always wear clothes. This fact favours the proximity between the two categories.

Wings or no wings?

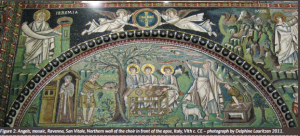

Would the main distinctive feature be the presence or the absence of wings? These are the only element which distinguishes angels from other holy characters. However, it might also happen that figures interpreted as angels are depicted wingless. On a sixth-century CE mosaic from San Vitale in Ravenna, one can see the contrast between the usual representation of winged angels flying above the scene of the Sacrifice of Abraham, where the ‘three visitors’ of Mamre appear as simple men, except for the halo which shines around their head (Figure 2). Inversely, personifications tend not to have wings. Exceptions exist, like the winged figure of ‘Power’ who is supporting David in his fight against Goliath in a tenth-century CE manuscript illustration (Figure 3).

Parallelism and (dis)similarity

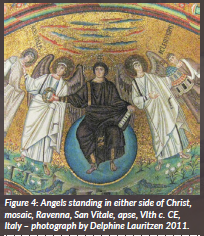

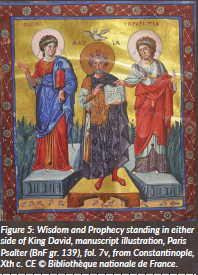

Some types of iconographical compositions underline the similarities between angels and personifications. This is particularly the case when one finds a central character surrounded on either side by two angels or two personifications. To take examples in the two monuments mentioned previously, the parallelism is striking while considering Christ enthroned with two angels in the apse of San Vitale (Figure 4) and King David between the personifications of ‘Wisdom’ and ‘Prophecy’ in the Psalter manuscript (Figure 5). In this context, the meaning and purpose of each work is singular, but the visual structure conveys the same type of interpretation: in both cases, angels and personifications exteriorise the idea carried by the main figure (Lauritzen 2022b).

Holy Wisdom

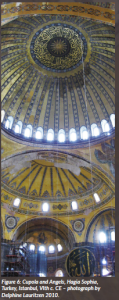

Among personifications of Virtues, Wisdom (Sophia) holds a special place. In the Ancient Hebrew texts, she personifies a specific aspect of God. Although much later in Byzantium, Christianity elaborates on the notion as the feminine counterpart of the divine Word (Logos), i.e. Christ. One should also reflect on Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, modern Istanbul. Named so from its origins in the Figure 2: Angels, mosaic, Ravenna, San Vitale, Northern wall of the choir in front of the apse, Italy, VIth c. CE – photograph by Delphine Lauritzen 2011. fourth century CE, the church was rebuilt under the emperor Justinian in the sixth century, becoming the greatest Christian building of the ancient Mediterranean world. It was declared a museum in 1934 and today is once more a mosque, as it was in previous centuries. Significantly, under the cupola of ‘Holy Wisdom’ stand four winged figures (Figure 6).

References

Lauritzen, D. (2020a) ‘ALATA Project. Ancient angels as key to modern society’, The Project Repository Journal, 7 (October), pp. 154–157. Available at: https://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk/html5/reader/ production/default.aspx?pubname=&edid=c2e20a7f-4d97-4ec6-b15e-ea040b9b71d7&pnum=154.

Lauritzen, D. (2020b) ‘La Psyché aux ailes d’ange d’une mosaïque d’Antioche’, Journal of Mosaic Research, 13, pp. 171–189. doi: 10.26658/jmr.782357.

Lauritzen, D. (2021 [forthcoming]), ed., Inventer les anges de l’Antiquité à Byzance : conception, représentation, perception, Paris, ACHCByz (Travaux et Mémoires 25/2).

Lauritzen, D. (2022a [forthcoming]), Aesthetics of Angels in Late Antiquity.

Lauritzen, D. (2022b [forthcoming]), ‘Les personnifications du Psautier de Paris comme marqueur d’une esthétique tardo-antique’, Le Psautier de Paris (BnF, Grec 139). Proceedings of the International Symposium, Paris, July 2–3, 2021.

Figure legends

Figure 1: Psyche, mosaic, Antakya, Mus. Hatay 892, Turkey, IIth c. CE – photograph by Kidder Smith 1938 colour n° 8219 © Antioch Expedition Archives, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Figure 2: Angels, mosaic, Ravenna, San Vitale, Northern wall of the choir in front of the apse, Italy, VIth c. CE – photograph by Delphine Lauritzen 2011.

Figure 3: Power, manuscript illustration, Paris Psalter (BnF gr. 139), fol. 4v, detail, from Constantinople, Xth c. CE © Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 4: Angels standing in either side of Christ, mosaic, Ravenna, San Vitale, apse, VIth c. CE, Italy – photograph by Delphine Lauritzen 2011.

Figure 5: Wisdom and Prophecy standing in either side of King David, manuscript illustration, Paris Psalter (BnF gr. 139), fol. 7v, from Constantinople, Xth c. CE © Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 6: Cupola and Angels, Hagia Sophia, Turkey, Istanbul, VIth c. CE – photograph by Delphine Lauritzen 2010.

PROJECT SUMMARY

The Marie-Curie project “The making of Angels in Late Antiquity: Theology and Aesthetics (ALATA)” combines texts (in Ancient Greek, Coptic, and Syriac) and images (chiefly ancient mosaics) to research the origins of Christian angels’ figures. This perspective sheds a new light on the key- issue of representation: how can one make the invisible visible?

PROJECT LEAD PROFILE

Dr Delphine Lauritzen was born in 1979. An alumna from the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris, she received her doctorate degree in Greek Studies from Sorbonne University (Paris-IV) in 2009. After a EURIAS Early Stage in Bologna and a Fernand-Braudel in Paris, she was awarded a MSCA grant to explore new paths in her field of expertise, literature and arts of Late Antiquity.

PROJECT PARTNERS

The ALATA project was implemented at Sorbonne University, in the CNRS-joined research unit “UMR 8167-Orient et Méditerranée”, section “Monde Byzantin”. The high concentration of scholars who work on the various aspects of Byzantine civilisation combined with the many resources of Parisian academic life were great assets for the project.

CONTACT DETAILS

Dr Delphine Lauritzen Institut d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, Collège de France, 52, rue du Cardinal Lemoine, 75005 Paris

Email: alataEU@gmail.com

https://www.orient-mediterranee.com/spip.php?article4502

FUNDING

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (MSCA-IF) grant agreement No.793760.