Water underpins health, prosperity and ecosystems. Yet demand is rising while climate change, urbanisation and industrial growth strain supplies. Conventional desalination and treatment methods—such as reverse osmosis, electrodialysis and thermal distillation—have expanded access, but they remain energy-intensive, often powered by fossil fuels and costly to operate. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation (SDIE) is emerging as a complementary route, a sunlight-powered method for producing clean water with minimal infrastructure and low operating costs.

What SDIE does

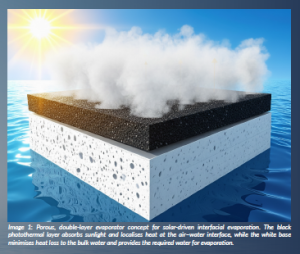

Traditional solar stills heat whole water volumes. SDIE concentrates heat at a thin layer where water, solid and vapour meet. A photothermal surface absorbs light and localises heat at the air–water interface; only a small mass of water is heated, so evaporation accelerates. With smart structures and materials, SDIE platforms can desalinate seawater, polish brackish sources and treat some industrial streams with far less energy input. Field and laboratory demonstrations report high evaporation rates under one sun, stable operation in saline feeds, and attractive economics when low-cost polymers and carbons are used. The approach is inherently modular and off-grid, which suits islands, remote communities and distributed reuse near the point of need.

What makes an efficient vapour generator

Performance is not only about absorbing sunlight; it is about managing heat and mass transport. Successful designs separate functions into layers and geometries. Double-layer and Janus structures feature a solar-absorbing, water-wicking top layer over a buoyant, thermally insulating base, reducing heat leakage to the bulk. Three-dimensional forms increase the true evaporative area and invite environmental energy; for example, gentle airflow can add sensible heat and sweep vapour. Hierarchical porosity, from macro-channels to nano-pores, promotes capillary supply, vapour escape and thermal insulation. Spatially patterned platforms can harvest convective and radiative losses from adjacent surfaces. Bio-inspired features—mimicking beaks, hair or leaves—tune liquid spreading, heat localisation and fouling resistance.

The working face is the interface

The water–solid–vapour interface does the work. Wettability sets how water arrives at, spreads over and departs from the hot surface. Hydrophilic domains feed the evaporation front; hydrophobic domains float the structure and limit back-conduction. Asymmetric wettability helps confine salt away from the optical absorber or encourages back-diffusion into the bulk. Porous polymer networks, including hydrogels, sustain capillary flow through interconnected channels. By adjusting their chemistry and cross-linking, one can shift the balance between bound, intermediate and free water, effectively lowering the effective enthalpy of vaporisation and lifting fluxes at a given irradiance. Thermal management matters just as much: thin absorbing layers, low-conductivity supports and non-contact gaps reduce losses to the reservoir, while hollow or lattice elements trap heat where it is useful.

Dealing with salt and real-world feeds

Long-term operation requires robust salt management and tolerance to additives. Strategies include directing crystallisation to sacrificial edges, creating cold/hot gradients that drive Marangoni flows to sweep deposits, and using ion-selective pathways that encourage ions to migrate away from the evaporating face. Some designs incorporate self-cleaning mechanisms, where salt crystals are periodically redissolved back into the bulk water, while self-healing polymers can restore performance and appearance after physical damage. With appropriate chemistries, photothermal layers can also host catalysts for degrading organic contaminants in the feed or for protecting surfaces against biofouling.

The SolWator contribution

Our hypothesis

We propose that controlling interfacial chemistry at micro- to nano-scales offers a lever to simultaneously improve evaporation rate, salt tolerance and durability. If we can engineer the triple-phase line—where liquid, solid and vapour meet—we can tune capillary pumping, heat localisation and solute transport.

Materials and sustainability

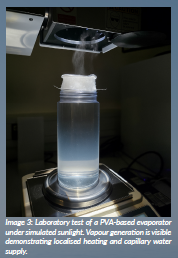

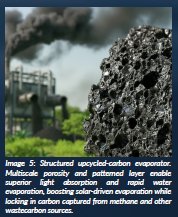

SolWator develops 3D hydrogel-carbon architectures that are light, porous and easy to manufacture. We began with poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) hydrogels as a hydrophilic matrix with stable networks that can be patterned in three dimensions. The PVA is physically cross-linked to maintain biocompatibility and avoid concerns related to microplastics. Other environmentally and biocompatible polymers, such as gelatin, alginate or chitosan, can also be used as alternatives depending on the desired mechanical or water-transport properties. For light absorption, we incorporate recycled and upcycled materials, such as graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) derived from captured CO₂, to align our purification process with circular economy goals. Carbonised materials and recycled or upcycled graphene from other resources can also be used, expanding the sustainability and circularity of the material supply. This choice of materials and fabrication methods ensures that SolWator functions as an environmental technology that not only addresses global challenges but also minimises its own footprint.

Structure and function

Our evaporator comprises a thin engineered photothermal top layer for strong solar absorption and a neat base with enhanced capillary pumping and thermal insulation. By varying the light absorber design and structure (such as thickness and porosity), we set steep, local temperature gradients at the surface without overheating the bulk of the evaporator. The hydrogel’s multiscale pores supply water continuously to the topside, while low conductivity and optional air gaps minimise downward heat loss. In addition to conventional hydrogel fabrication methods, nanoscale techniques such as electrospinning help SolWator achieve targeted properties in thermal management and water transport, allowing for precise control over pore architecture and surface morphology.

Interface-aware design

At the heart of SolWator is interface engineering. The radius of the meniscus that forms within micro-channels and around surface textures governs capillary pressure and thus the replenishment of the evaporation front. By patterning wettability and geometry—ridges, cavities and stripes of different chemistry—we shape the meniscus, stabilise thin films and route brine towards designated crystallisation sites away from the optical absorber. This also shortens the heat path to the interface, maintaining high interfacial superheat with modest energy input.

Thermal and salt management

We integrate several mechanisms: insulating supports to limit conduction; closed-porous struts that trap air and reduce radiation; open pores that create capillary forces and act as a water pump; staged height differences that recover convective and radiative losses between neighbouring surfaces; and salt-routing edges where crystals form and detach without blocking the active area. In high-salinity tests, we observe sustained performance without surface blinding, consistent with designed back-diffusion and edge precipitation.

From lab to field

The ERC Starting Grant enables us to link fundamental interfacial physics with manufacturable designs. Under the leadership of Assoc. Prof. Ali Sadaghiani (PI, thermal-fluid and interface engineering), the project develops printable formulations for structured hydrogels and carbon aerogels with tailored porosity, cross-linking and surface chemistry to optimise capillary transport, light absorption and mechanical resilience. Materials development and characterisation are led by Dr Sajad Sorayani (Researcher, materials scientist), ensuring robust design–property correlations and sustainable material selection. The team advances scalable printing strategies for reproducible module fabrication. Optical and thermal diagnostics quantify interfacial temperature, film thickness and meniscus shape, while accelerated ageing studies address fouling, mechanical fatigue and UV stability. Prototype modules are being evaluated under natural sunlight with varying winds, salinities and organic loads. The goal is a durable, repairable, low-cost evaporator cassette that can slot into a multistage assembly for latent-heat reuse or operate as a standalone unit for small-community supply.

Why interface engineering matters

Breaking performance plateaus

Reported evaporation rates under one sun already exceed early theoretical limits because designs reduce effective enthalpy and harvest environmental energy. Interface control offers further gains by keeping the active area wet, thin and clean while concentrating heat where it does the most work. Open pores, capillary channels and micro-structured surfaces help sustain continuous water flow, manage local salt accumulation and maintain high interfacial superheat, allowing the system to approach thermodynamic limits without compromising stability.

Durability and maintenance

Real feeds include salts, surfactants, dyes and fine particulates. Devices encounter UV, temperature swings and biofilms. Interfaces that resist salt adhesion, shed deposits and self-heal after minor damage extend service intervals and reduce lifetime cost—critical for off-grid use or remote applications. Material choices and cross-linking strategies further enhance chemical and mechanical resilience, ensuring sustained performance over months or years without frequent intervention.

Scalability and cost

Materials such as PVA and upcycled carbons are inexpensive, safe and widely available. Designs that rely on geometry and chemistry rather than exotic coatings favour scale-out manufacturing. Interface-driven water routing also simplifies module hydraulics, which helps maintenance and training in the field.

Integration and multifunctionality

The same interfacial controls that enhance evaporation can host photocatalysts or sorbents for contaminant removal or integrate with multistage condensers that recapture latent heat. In SolWator, we are coupling interface-aware evaporators with selective condensers to improve overall energy efficiency and distillate quality. Interfaces thus become multifunctional platforms, simultaneously supporting evaporation, purification and fouling management.

Outlook

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation does not replace all conventional treatment, but it adds a robust tool to the mix—particularly where grid power is scarce, brines are challenging or small, decentralised systems are preferred. By focusing on the water–solid–vapour interface and using sustainable materials, SolWator aims to convert sunlight into clean water more efficiently, reliably and at a lower cost. In a century defined by water security, this is practical optimism: disciplined physics and design, deployed where it matters.

Project summary

Water scarcity affects around two-thirds of people, demanding new, practical solutions. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation (SDIE) uses sunlight to produce fresh water with higher efficiency than conventional methods. SolWator examines what happens right at the water–air interface, combining high-resolution temperature imaging, optical diagnostics and computer modelling to reveal how heat and vapour behave at microscopic scales. Guided by this evidence, we design interfaces that speed evaporation and conserve heat, enabling scalable, durable and low-cost clean-water systems. The insights can strengthen desalination and have knock-on benefits across energy, manufacturing and environmental technologies.

Project lead profile

Dr Ali Sadaghiani, Associate Professor and Anniversary Fellow at the SMaRT SurFace Research Group, University of Birmingham, leads the Smart Research Group specialising in phase-change heat transfer and advanced surface engineering. With degrees in mechanical, mechatronics and thermofluidics, his ERC-funded research advances energy-efficient technologies across hydrogen propulsion, solid-state batteries, desalination and anti-icing systems through interdisciplinary surface and thermal-fluid innovations.

Project contacts

Dr Ali Sadaghiani PhD

School of Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT

Email: a.sadaghiani@bham.ac.uk

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101164610).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Image 1: Porous, double-layer evaporator concept for solar-driven interfacial evaporation. The black photothermal layer absorbs sunlight and localises heat at the air–water interface, while the white base minimises heat loss to the bulk water and provides the required water for evaporation

Image 2: Interface-engineered evaporator in contrasting environments. The design supports clean-water production from diverse sources, including polluted or saline feeds, while maintaining thermal efficiency and structural integrity.

Image 3: Laboratory test of a PVA-based evaporator under simulated sunlight. Vapour generation is visible demonstrating localised heating and capillary water supply.

Image 4: Experimental setup for thermal and evaporation diagnostics. Controlled illumination replicates solar input to quantify interfacial temperature and water flux under laboratory conditions.

Image 5: Structured upcycled-carbon evaporator. Multiscale porosity and patterned layer enable superior light absorption and rapid water evaporation, boosting solar-driven evaporation while locking in carbon captured from methane and other waste-carbon sources.