The GIAPHAGE project, funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant, is focused on revealing the unknown biology and ecology of large bacterial viruses, phages, using a unique set of isolates. It also aims to clarify how abundant large phages are and what role they play in the environment.

Microbes keep Earth’s life systems running by driving the chemical cycles that make life possible (Falkowski, Fenchel and DeLong, 2008). Viruses, in turn, shape these microbial communities—they can change which microbes are present, what their genes are, and even how they use energy (Suttle, 2007). Still, we know surprisingly little about how viruses and their microbial hosts interact. Current methods, while evolving, still have limitations for measuring and describing these relationships. Only recently have researchers begun to reveal how important viruses are in controlling microbial systems, for example, by reprogramming the metabolism and gene activity of the bacteria they infect (Breitbart et al., 2018).

In the oceans, most of the living matter is microbial, and it’s becoming clear that viruses, along with other microbes, are both drivers and responders to global climate change. To understand and predict how microbes will affect carbon cycling and the ‘microbial loop’ under future climate conditions, we need more details about virus–host interactions. This knowledge is essential if we want to include viruses in climate change models (Danovaro et al., 2011). In short, viruses are central players in ecosystems, and ignoring them gives us an incomplete picture of how life and climate are connected.

When a virus infects a bacterium, the cell stops acting like its original self and instead becomes what scientists call a virocell—a cell reprogrammed to serve the virus. In this state, much of the cell’s metabolism is redirected to support viral replication rather than the bacterium’s normal functions. This shift can have far-reaching effects: if many of the most common bacteria in an environment are infected at once, their collective change in metabolism can alter how nutrients and energy flow through the ecosystem. In other words, viral infections don’t just affect individual microbes—they can reshape whole microbial communities and, ultimately, the larger environment they are part of.

Beyond ecology, newly discovered viruses are also opening doors in biotechnology. Their unique enzymes and genetic features are being explored as novel tools for medicine, molecular biology and even sustainable technologies. This makes the study of viruses important not only for understanding nature but also for creating future innovations.

Megaphage genome size exceeds those of the smallest bacteria

Viruses that infect bacteria (in short phages) are ubiquitous and the most numerous entities on our planet (e.g. Clockie et al., 2011). Although phage research benefits from ever-growing sequence data, the lack of real-life biological significance and connection to biological functions is increasing.

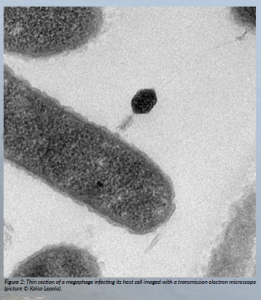

Recently, researchers discovered a group of unusually large viruses called megaphages by analysing DNA from many sources, including the environment, animals and humans (Al-Shayeb et al., 2020), and in another study, from the ocean (Michniewski et al., 2021). These viruses stand out because their genomes are enormous—over 600 000 base pairs, which is bigger than the genomes of some bacteria.

Despite their impressive size, very little is known about how these giant phages actually live and function. So far, no one has been able to isolate them in the lab, which means their biology is still largely a mystery and has fuelled much speculation.

The GIAPHAGE project is tackling some of the most fundamental questions about megaphages by working with the very first megaphage isolates. The research provides compelling evidence that megaphages are genuine biological entities, not just artefacts of metagenomic assembly. The project explores not only their biology but also their ecology—how common they are, where they live and what roles they play in ecosystems. By doing so, GIAPHAGE will expand our understanding of viral diversity and may also uncover new virus-derived tools that could be useful in biotechnology.

Megaphages have been thought to be rare, but our ongoing work suggests they may actually be much more common. This means they could have a far greater influence on ecosystems than we realised. By investigating their ecological roles, the project aims to challenge and refine current views of how these giant viruses interact with microbial ecosystems. By studying how megaphages take over their host bacteria and what happens when those hosts burst, we can better understand their impact on the movement of elements and nutrients in the environment.

With the unusually large coding capacity, megaphages may boost host metabolism through auxiliary metabolic genes and help break down complex biomass. Uncovering the molecular strategies they use to take over their hosts is expected to reveal novel viral enzymes and regulatory elements with potential applications in biotechnology, including genome engineering and microbial system design.

Aims of GIAPHAGE

- Uncover how megaphages work by studying the first-ever isolates that can be grown in the lab.

- Explore how megaphages interact with their bacterial hosts under natural conditions, and what happens inside an infected cell when the virus takes over.

- Find out how vastly megaphages infect different bacterial species.

- Investigate how megaphages compete with other viruses by setting up controlled ‘virus–virus competition’ experiments.

- Find out where megaphages occur and how common they are in the environment, testing where these giant viruses are especially enriched.

References

Al-Shayeb, B. et al. (2020) ‘Clades of huge phages from across Earth’s ecosystems’, Nature, 578(7795), pp 425–431. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2007-4.

Breitbart, M., Bonnain, C., Malki, K. and Sawaya, N.A. (2018) ‘Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm’, Nature Microbiology, 3(7), pp. 754–766. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0166-y.

Clokie, M.R., Millard, A.D., Letarov, A.V. and Heaphy, S. (2011) ‘Phages in nature’, Bacteriophage, 1(1), pp. 31–45. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.1.14942.

Danovaro, R., Corinaldesi, C., Dell’Anno, A., Fuhrman, J.A., Middelburg, J.J., Noble, R.T. and Suttle, C.A. (2011) ‘Marine viruses and global climate change’, FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 35(6), pp. 993–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00258.x.

Falkowski, P.G., Fenchel, T. and DeLong, E.F. (2008) ‘The microbial engines that drive Earth’s biogeochemical cycles’, Science, 320(5879), pp. 1034–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1153213.

Michniewski, S., Rihtman, B., Cook, R., Jones, M.A., Wilson, W.H., Scanlan, D.J. and Millard, A. (2021) ‘A new family of “megaphages” abundant in the marine environment’, ISME Communications, 1(1), 58. doi: 10.1038/s43705-021-00064-6.

Suttle, C.A. (2007) ‘Marine viruses — major players in the global ecosystem’, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 5(10), pp. 801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750.

Project summary

The Life of Giant Phages (GIAPHAGE) project is focused on revealing the unknown biology and ecology of large bacterial viruses, phages, using a unique set of isolates. It also aims to clarify how abundant large phages are and what role they play in the environment. GIAPHAGE started at the end of 2023 and is funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant.

Project partners

The GIAPHAGE project is hosted by the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, and Nanoscience Center, University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Project lead profile

Elina Laanto is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, and Nanoscience Center, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her work focuses on the biology of novel large phages, their host interactions and ecology. In 2019, she received an Academy of Finland postdoctoral funding to study alternative phage infection strategies. The ERC Starting Grant 2023 will open new directions in phage research, focusing on the previously uncultivated megaphages.

Project contacts

Elina Laanto

Email: elina.laanto@jyu.fi

Web: www.jyu.fi/en/research-groups/phage-biology-group

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101117204)

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: One of the locations used for megaphage sampling in northernmost Finland. Water sample is being taken by postdoctoral researcher Karyna Karneyeva.

Figure 2: Thin section of a megaphage infecting its host cell imaged with a transmission electron microscope (picture © Kaisa Lepola).

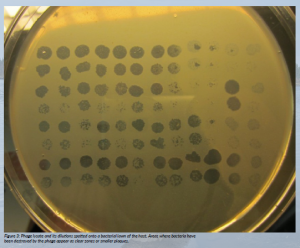

Figure 3: Phage lysate and its dilutions spotted onto a bacterial lawn of the host. Areas where bacteria have been destroyed by the phage appear as clear zones or smaller plaques.