- Dieback of tropical forests is a concern for modern climate change.

- SIM-EARTH analysed a past mass extinction event where forests were destroyed.

- These findings can help us better prepare for the future.

The ‘Great Dying’: an ancient climate change event

Roughly 252 million years ago, our planet experienced the most devastating biological crisis in its history—the Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction, also known as ‘the Great Dying’. This cataclysm wiped out up to 94% of marine species and around 70% of terrestrial vertebrate families, reshaping life on Earth forever. While the disappearance of animals has long been recognised, recent research has revealed that land plants—including vast tropical forests—also suffered catastrophic losses.

Before the extinction, tropical rainforests thrived across the supercontinent Pangaea, functioning much like they do today: as powerful carbon sinks that absorbed atmospheric CO₂ and stabilised the climate. However, a chain reaction triggered by massive volcanic eruptions—the Siberian Traps in what is now Russia—released enormous volumes of greenhouse gases. Global surface temperatures soared by 6–10 °C within tens of thousands of years, overwhelming many species’ ability to adapt.

What puzzled scientists for decades was not the extinction itself, but what followed. Usually, after such dramatic climatic disruptions, Earth’s environment recovers within several hundred thousand years. Yet following the Great Dying, super-greenhouse conditions persisted for over five million years—far longer than expected. The question of why the planet remained locked in a hothouse state is very important, as human CO₂ emissions continue to warm our world today.

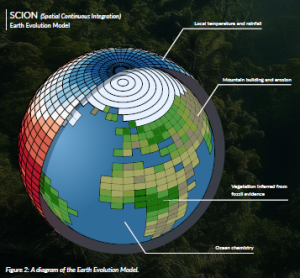

Our SIM-EARTH project is uniquely capable of answering this question, using our ‘Earth Evolution’ computer model that is capable of simulating climate and biosphere changes over thousands to millions of years. By re-running this event in our model, we found that the collapse of land vegetation, particularly tropical forests, fundamentally weakened Earth’s ability to regulate its climate. Without these carbon-hungry forests, the planet lost one of its most effective mechanisms for drawing down atmospheric CO₂, allowing extreme warming to persist far beyond the initial volcanic trigger.

How to re-run an extinction event inside a computer

To investigate how terrestrial vegetation responded to this ancient crisis, we reconstructed the distribution and composition of plant biomes across different climate zones—from tropical and subtropical forests to temperate and arid landscapes—spanning millions of years before and after the extinction. This involved a concerted effort to locate, classify and compile all available plant fossil evidence throughout this time period and to populate our simulated planet with realistic plants across its land surface.

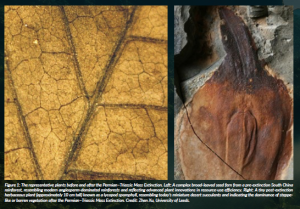

Prior to the crisis, dense peat-forming forests and rich tropical ecosystems flourished near the equator. These forests were highly efficient at sequestering carbon through photosynthesis and storing it as organic matter, playing a central role in the global carbon cycle. But as temperatures rapidly rose, these ecosystems collapsed. The fossil record shows a striking ‘coal gap’: an interval of millions of years with almost no evidence of coal-forming vegetation, indicating the near-total disappearance of tropical forests. In their place, Earth’s landscapes became dominated by tiny lycopods—plants just a few centimetres tall—while larger plant species survived only in cooler polar or high-altitude refuges. It took over five million years for forests to re-establish themselves, and even then, the new vegetation was less productive and less efficient at carbon fixation.

This shift had profound consequences for the planet’s global chemical cycles. The reduction in global plant biomass and productivity severely disrupted the carbon cycle, slowing the removal of CO₂ from the atmosphere. Using our Earth Evolution Model, we determined that the rate at which plants convert CO₂ into biomass plummeted after the extinction, and this decline alone was enough to prolong extreme greenhouse conditions for millions of years. Only when vegetation slowly recovered and spread back into tropical climates did the Earth begin to cool and stabilise. This finding fundamentally changes how we understand mass extinctions. It shows that plants are not passive victims of global change but active participants in Earth’s climate regulation. When vegetation collapses, the consequences ripple across the entire Earth system, affecting the land surface, atmosphere, oceans, and even the evolution of life.

What can we learn from the past for our future?

While the Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction unfolded over hundreds of thousands of years, the lessons it offers are relevant today. Human activity—particularly the burning of fossil fuels—is driving climate change hundreds of times faster than during the Great Dying. The world’s rainforests, which store vast amounts of carbon and regulate global weather patterns, are under mounting stress from rising temperatures, deforestation and land-use change.

Our research underscores a sobering reality: there are tipping points in the Earth system that have been passed before, and from which recovery took far greater than human timescales. In this ancient scenario, even halting greenhouse gas emissions was not enough to reverse the trend—the Earth remained hot for thousands of millennia.

Yet, there is hope. We are not living 250 million years ago. Modern rainforests may be more resilient to temperature stress than their ancient counterparts. Their evolutionary history, genetic diversity and complex ecological interactions could provide a stronger buffer against warming. However, all resilience has limits. There will exist thresholds where we may still see abrupt ecological collapses similar to those that reshaped the planet 252 million years ago. The key question is where those thresholds lie.

This insight is guiding our next steps. Through the SIM-EARTH project, we are now expanding our work to examine how plant evolution through geological time has influenced these tipping points, from the first forests some 400 million years ago to the climate warming events of the last 50 million years, after the evolution of flowering plants and then grasses. Understanding these long-term feedbacks will help us predict how terrestrial ecosystems might respond to future warming, and inform strategies for mitigation and adaptation.

As we stand at a crossroads in the ‘Anthropocene’, the past offers both a warning and a guide.

Preserving and restoring forests is not simply an act of conservation—it is an essential strategy for sustaining a stable climate.

By learning from ancient mass extinctions, we can better understand how our planet’s biosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere co-evolve—and how humanity can help steer that evolution toward a sustainable future.

Conference

The annual ‘Life and Planet’ conference runs in London every summer. See lifandplanet.com.

Project summary

This study is part of the SIM-EARTH project, a research initiative that integrates fossil records, plant evolutionary data, geochemical proxies and advanced Earth system models to investigate the long-term co-evolution of life and climate. By combining fieldwork, fossil analysis and high-performance simulations, SIM-EARTH aims to uncover how terrestrial ecosystems have shaped—and been shaped by—global environmental change, from the deep past to the present and into the future.

Project researcher profiles

This work was led by Zhen Xu, Research Fellow at the University of Leeds, working in the Earth Evolution Modelling Group led by Professor Benjamin Mills.

Project contacts

Dr Xu

Email: z.xu@leeds.ac.uk

Professor Mills

Email: b.mills@leeds.ac.uk

Web: earthevolutionmodelling.com

Funding

This project has been funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Guarantee programme (Grant agreement No. EP/Y008790/1).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or UKRI. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: The representative plants before and after the Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction. Left: A complex broad-leaved seed fern from a pre-extinction South China rainforest, resembling modern angiosperm-dominated rainforests and reflecting advanced plant innovations in resource-use efficiency. Right: A tiny post-extinction herbaceous plant (approximately 10 cm tall) known as a lycopod sporophyll, resembling today’s miniature desert succulents and indicating the dominance of steppe-like or barren vegetation after the Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction. Credit: Zhen Xu, University of Leeds.

Figure 2: A diagram of the Earth Evolution Model.