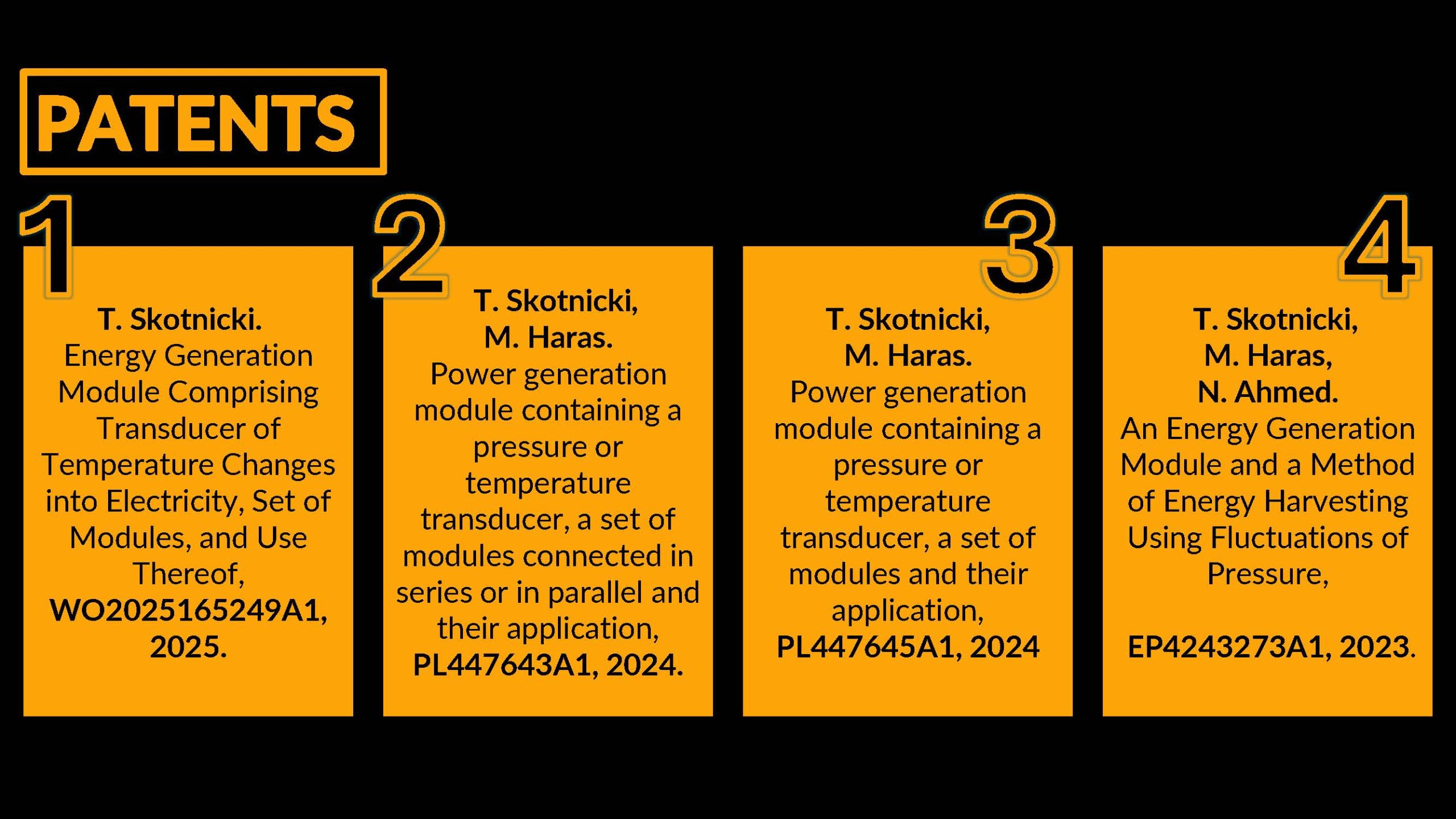

SelF-powerIng electroNics – the Key to Sustainable future” (SFINKS)

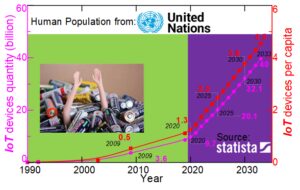

Figure 1. Conventional powering of Internet of Things is challenging regarding quantity, portability and size.

Technology has transformed our world. We carry more computing power in our pockets than once existed in entire research labs. Smartwatches track our health, sensors monitor cities, satellites observe our planet, and billions of electronic devices quietly assist us every day. Yet even the cleanest and most efficient technologies have a hidden environmental cost. Modern society produces trillions of disposable batteries each year. They power our remote controls, sensors, wearable health trackers, smart home systems, and countless Internet of Things devices (IoT) (see Figure.1). Most of these batteries eventually end up in landfills, where they leak harmful substances into soil and water and are extremely difficult or expensive to recycle. As our digital world expands, so does the size of our electronic footprint. We are now in a situation where technology designed to make the world smarter and greener is simultaneously contributing to one of the fastest-growing forms of pollution. This raises a critical question: can we make smarter electronics without relying on disposable power sources? Can we build devices that operate forever without replacing or recharging batteries?

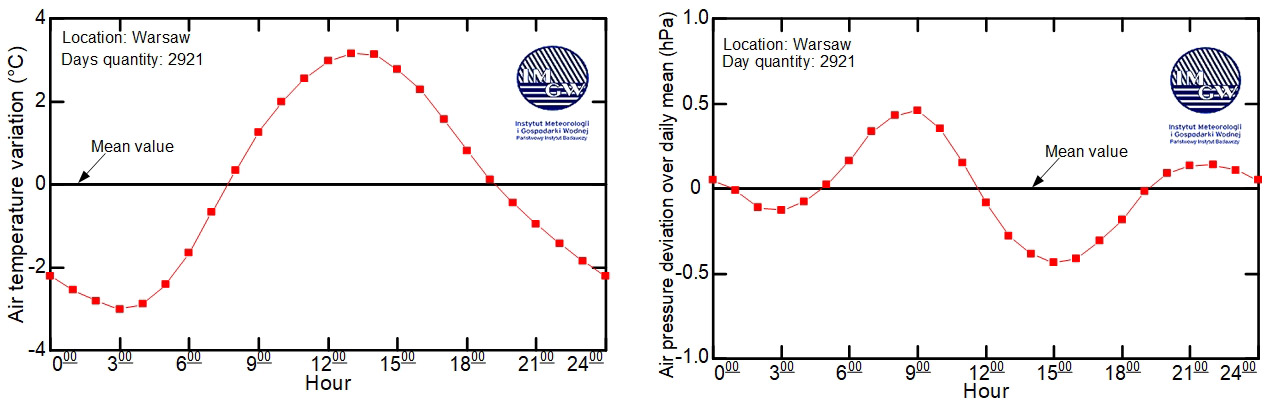

A surprising answer may already exist in the environment around us. When people think of renewable energy, they usually mention sunlight, wind, or ocean tides. However, nature offers another source of energy that is less obvious but constantly present. Just as seas rise and fall in daily cycles, the atmosphere also experiences its own type of tides. Atmospheric pressure and temperature fluctuate rhythmically every day (see Figure 2). These changes are small but reliable. They never stop, not at night, not in winter, not during storms, and they occur everywhere on the planet. Even more astonishingly, similar atmospheric variations occur on other planets such as Mars and Venus. The atmosphere behaves like a global heartbeat, offering tiny but continuous packets of natural energy. If we could learn to harvest this energy and transform it to electricity, we could open the door to truly perpetual, maintenance-free electronics.

Figure 2. Ubiquitous, omnipresent and always delivering natural temperature and pressure tides – source energy for SFINKS.

This idea is much older than modern electronics. Over 400 years ago, the Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel designed a remarkable device called the Eltham Perpetuum clock. It required no winding and ran continuously using only the natural fluctuations in temperature and pressure in the surrounding air. A later development, the Beverly Clock from 1864, has been running for over 150 years without anyone resetting or powering it. These inventions proved that atmospheric tides can power mechanical devices indefinitely. However, they were large, mechanically complex, and limited to moving gears and clock hands. For centuries no technology existed to miniaturize the concept, integrate it into electronics, or convert environmental energy into electrical power at small scale.

Today this is changing thanks to SFINKS, a project funded by the European Research Council. SFINKS aims to transform the centuries-old principle of atmospheric energy harvesting into a modern microtechnology capable of powering electronic devices. In contrast to conventional energy harvesters, SFINKS draws energy from an omnipresent source, making direct interaction with the energy source implicit rather than imposed. Traditional energy harvesters typically require either physical contact or precise alignment with the energy source: thermoelectric, piezoelectric, and electrostatic systems rely on low-loss direct contact, while photovoltaic cells must be carefully oriented toward incoming light. SFINKS, by comparison, operates while being fully immersed in the energy source itself. As a result, it eliminates the need for orientation, mechanical coupling, or strict contact conditions, offering a fundamentally more flexible and robust approach to energy harvesting.

With this breakthrough, SFINKS is developing tiny generators manufactured using silicon technology, similar to the processes used to create modern microchips. These miniature devices will combine mechanical elements, temperature-sensitive components, and electricity-generating materials into a single integrated structure. The goal is not just to build another type of energy harvester, but to create the first miniature generator that works everywhere and always, without needing sunlight, wind, vibration, or user interaction. Atmospheric tides are universal and require no installation direction or environmental tuning, which makes them an ideal power source for electronics that must operate autonomously.

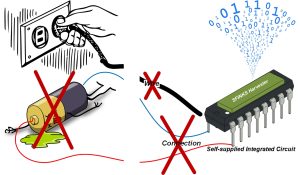

Figure 3. Energy-autonomous electronics—the holy grail that SFINKS can provide.

One of the areas that could benefit most from this technology is the Internet of Things. Today most of these devices run on small batteries that must eventually be replaced, which is costly, labour-intensive, and environmentally damaging. In large-scale installations, technicians may need to replace thousands of batteries every year, often in locations that are difficult to access. Without a viable alternative to batteries, the rapid expansion of IoT risks producing a silent environmental crisis. SFINKS could eliminate this limitation entirely. A sensor equipped with a SFINKS micro-generator could run indefinitely, generating its own energy from the surrounding atmosphere without any maintenance (see Figure 3). The sensor would simply exist and work, always on, always gathering data, just as natural systems function without human intervention. This would allow smart cities to expand without mountains of electronic waste, and factories to monitor machinery continuously without downtime. Medical wearables and environmental monitors could operate for years without recharging. Technologies that normally require constant attention could become self-sustaining. SFINKS harvester will pave the way towards drop-it-and-forget-it a Holy Grail for the next generation electronics (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Drop-it-and-forget-it electronics—a dream that is coming true, thanks to SFINKS.

The potential of this technology reaches far beyond Earth. On Mars and Venus, temperature and pressure vary throughout the day in ways that are even more pronounced than on Earth. Space missions must currently rely on solar panels, batteries, or nuclear systems, all of which have drawbacks. Solar power depends on sunlight and can fail when panels accumulate dust. Batteries take up space and limit mission lifetime. Nuclear sources are effective but heavy, expensive, and difficult to deploy. A tiny generator capable of harvesting atmospheric tides could power scientific instruments for years without external energy. SFINKS envisions future missions in which small autonomous weather stations, atmospheric probes, or surface sensors operate on Mars indefinitely, taking advantage of the natural planetary environment. This would allow long-term monitoring that is currently impossible or prohibitively costly. One of the project’s dreams is to send SFINKS-powered devices on a future Mars mission and demonstrate that perpetual atmospheric powering is not only possible on Earth, but also on another world.

Figure 5. 400 years of SFINKS History, Future Stability, and Size.

If successful, SFINKS could fundamentally change how we think about powering electronics. Instead of asking how we recharge devices, we could ask how devices recharge themselves. Technology could shift from a system that needs constant human care to one that behaves more like a living organism—adapted to its environment, self-sustaining, continuous. Devices could last not months or years, but decades, and billions of batteries would no longer be needed. The atmosphere has been pulsing with energy since the beginning of the planet. For centuries that energy powered only a few unusual clocks. Now, with advances in micro-engineering and materials science, it may soon power the next generation of electronics, both on Earth and beyond (see Figure 5).

References:

[1] M. Filipiak, M. Haras, B. Stonio, N. Ahmed, K. Pavlov, L. Łukasiak, T. Skotnicki, CMOS-compatible fabrication of bi-stable thin-film silicon membranes for quasi-perpetual piezoelectric energy harvester, in: Smart Materials for Opto-Electronic Applications, SPIE, Prague, Czech Republic, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3058380

[2] [keynote] T. Skotnicki, N. Ahmed, L. Łukasiak, B. Stonio, M. Filipiak, M. Haras, SFINKS -SelF-powerIng electroNics – the Key to Sustainable future, in: Smart Materials for Opto-Electronic Applications, SPIE, Prague, Czech Republic, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3058382