Next year, the EU-funded nature conservation project GRIP on LIFE IP in Sweden will conclude, marking more than eight years of intensive work. The project has focused on forestry practices that show consideration for water and on improving habitat conditions for animals and plants in wetlands and watercourses. GRIP on LIFE IP can now present several noteworthy results.

GRIP on LIFE IP is one of the larger EU-funded LIFE projects implemented in Sweden in recent years, having started in 2017. Unlike most other ongoing LIFE projects, however, GRIP on LIFE is primarily aimed at enhancing knowledge, with only a limited proportion of its activities devoted to the physical restoration of natural environments.

“Our objective has been to generate new knowledge and to disseminate information on forestry practices that consider water, as well as on how environmental conditions for various species in watercourses and wetlands can be improved. Knowledge building has included follow-up studies of previous restoration efforts, and we have conducted specific research. We have also tested new methods and practices. In addition, we have worked to strengthen collaboration among different stakeholders. Establishing effective collaboration is particularly important when there are differing opinions on the optimal use of forests and water,” says Gunilla Oleskog, Project Manager for GRIP on LIFE.

The dissemination of knowledge has, in turn, involved a wide range of activities aimed at providing advice and evidence-based information to GRIP on LIFE’s target groups, including, among others, forest owners and forestry professionals. As the project concludes at the turn of the year, numerous insights and conclusions can now be shared across wetlands, watercourses, environmental considerations in forestry, working methods and practices, collaboration, and school and education.

“Our hope is that these results will be put to practical use. Even though our work has been conducted within a Swedish context, many of the findings are applicable in other countries as well,” Oleskog concludes.

A selection of the key results from GRIP on LIFE are presented in the following.

Working methods and practices

GRIP on LIFE is a multifaceted project. The mandate to serve as a knowledge-enhancing initiative has led the project to test new ways of working and develop new methods.

Among other things, GRIP on LIFE, together with the Swedish Forest Agency and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), has developed an advanced digital mapping tool—the Forest Water Map—which makes it easier to assess the risk of negative impacts on lakes and watercourses during forestry operations. The Forest Water Map shows where surface water can be expected within the area where a forestry measure is planned, while providing an understanding of how water moves between the area in question and downstream lakes and watercourses. The map also indicates the size of the water flow. In addition, it serves as support for the design of protective measures in connection with ditch cleaning and protective ditching, as well as for the dimensioning of culverts. The Forest Water Map can also be a valuable tool in wetland restoration. The map is freely available.

GRIP on LIFE has also developed various prioritisation tools and digital maps. One example is a mapping tool designed to facilitate the identification of sites in southern Sweden where wetlands can be created or restored. These maps—or more precisely, new map layers—are part of an existing GIS-based wetland map. The new layers make it possible to locate potential wetland sites and to assess where wetland measures would have the greatest effect, based on five ecosystem services: reduced greenhouse gas emissions, increased biodiversity, nutrient retention, reduced flood risk and groundwater recharge.

Another example of a combined working method and digital mapping tool is a prioritisation tool for restoration measures in watercourses in southwestern Sweden. The method, called the Integrated Water Action Plan, brings together in one place the identified needs for measures linked to connectivity (migration barriers) and ranks them in order of priority. The plan is designed as a geodatabase with a GIS layer, that is, a digital map. Its purpose is primarily to serve as a basis for those working with water-related restoration measures.

When it comes to working methods, it is worth mentioning a specific model used in southeastern Sweden to support landowners in wetland restoration and construction. A recurring criticism in Sweden is that landowners often find it difficult to know which authority to contact, since this depends on the type of wetland measure involved. The legislation and regulations surrounding water operations are also often perceived as complex, and it can be challenging to obtain clear information about the different grants available for such measures.

The purpose of the GRIP on LIFE model is to simplify and improve the process for landowners and, ultimately, to enable the restoration of more wetlands. In practice, the model makes it easy for landowners to register their interest in establishing or restoring a wetland. The county administrative board in this part of Sweden then responds to the registration with concrete advice and guidance on the appropriate support schemes and the relevant authority. Landowners can also receive on-site advice on how to implement the measure. In some cases, GRIP on LIFE has also financed the physical restoration work.

The model has proven successful and stands as a good example of how a systematic, yet straightforward method can make a real difference.

Wetlands

In Sweden, the restoration of drained wetlands has come into focus in recent years. This is especially important since drained wetlands can emit large amounts of greenhouse gases as the peat decomposes. Wetlands are also recognised for their rich biodiversity and for their capacity to regulate water flows in the landscape.

Almost one quarter of all original wetlands in Sweden have disappeared during the past century in order to create more agricultural and forestry land. For this reason, wetlands need to be restored on a large scale to address several climate and environmental challenges, according to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

GRIP on LIFE has, to some extent, carried out wetland restoration, but the project has primarily focused on acquiring and disseminating knowledge about the benefits that functioning wetlands provide and restoration practices. One example is a review of the advantages and disadvantages of different techniques for restoring wetlands. GRIP on LIFE examined more closely the methods of ditch infilling, ditch plugs and ditch infilling in combination with plugs. One conclusion from this review was that ditch infilling often needs to be complemented with plugs to reduce the risk of erosion, ensure adequate water flow and achieve the desired water level.

Now, several years later, GRIP on LIFE has partly arrived at an approach where restoration does not rely solely on ditch infilling and ditch plugging. As experience has grown, it has become evident that, in some cases, the best solution is to restore the natural thresholds that once retained water in the landscape. A threshold, originally formed by the inland ice, prevents water from draining away. However, as the demand for more forest and arable land increased in Sweden during the last century, many thresholds were dug out and wetlands were drained. GRIP on LIFE’s guiding principle is to re-establish the natural hydrology. The choice of restoration method—or a combination of methods—must therefore be based on the site’s historical conditions and on the restoration objectives.

GRIP on LIFE has also investigated the impact of ditch infilling on water quality. Our study of a watercourse in central Sweden shows that water quality was somewhat degraded when ditches were filled in on two adjacent wetlands. However, the negative effects were local and were assessed to be only initial. The study also demonstrates that there was no significant increase in methylmercury, as had been feared. On our experimental site in northern Sweden, we filled in the ditch system in a mire and observed significantly increased concentrations of organic material, nutrients and a lower pH in the ditch outlets after the ditch filling. These effects persisted even after four years of measurements. However, the mire’s ability to retain water improved.

Restoring wetlands can have a major positive impact on the habitats of many species. Many species are also able to establish themselves quickly after restoration. This is demonstrated by a unique series of field inventories conducted by GRIP on LIFE in cooperation with a county administrative board in southernmost Sweden.

The wetland in question was restored in 2019 and inventoried once before the measure and twice afterwards, in 2021 and 2024. The surveys covered the number of species of birds, vascular plants, amphibians, dragonflies, butterflies, Sphagnum moss, beetles and other insects. Two years after the restoration, in 2021, the inventories showed a marked increase in the number of species. Among other things, the number of wetland bird species increased from 24 to 34. The group of other insects more than doubled.

The third inventory in 2024, however, showed that the increase in the number of species had levelled off, and that some species recorded in 2021 were no longer found in 2024. This was the case, for example, for the number of bird species, which had decreased to 19. One possible explanation is the cold and rainy spring of 2024, which negatively affected bird life.

GRIP on LIFE has also conducted follow-ups on how biodiversity has developed after the restoration of several drained peatlands (mires) in northern Sweden. Here, field inventories have examined the occurrence of wetland birds, monitored the development of typical plant species and measured the growth of Sphagnum moss. Sphagnum mosses are crucial in mire ecosystems, as they build up the mires through the accumulation of peat. The results from these follow-ups also suggest that biodiversity has increased after restoration. However, the compilation was not finalised at the time of publication of this article.

The impact of drained peatlands on the climate has also been studied within GRIP on LIFE. Researchers at the University of Gothenburg, commissioned by the project, published a study showing that restored mires can achieve carbon balances and methane emissions similar to those of natural mires. Over a three-year period, the researchers examined two restored mires and compared them with pristine mires to assess whether restored sites exhibit the same carbon dioxide and methane fluxes as natural ones. The conclusion is that mire restoration has considerable potential to prevent carbon dioxide emissions and possibly to re-establish their role as carbon sinks, without causing major methane emissions. Restoration should aim for stable water levels close to the ground surface, as is usually the case in intact mires. This protects the peat in the mire from decomposition and can allow for new peat accumulation over the long term—in other words, enabling the mire to act as a carbon sink—without a major risk of high methane emissions.

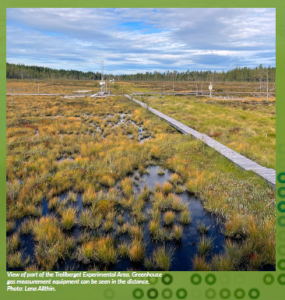

GRIP on LIFE has also established a forestry demonstration and research site—the Trollberget Experimental Area—in northern Sweden, together with the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and the forest owner Holmen Forest. At the site, interpretive trails have been established with GRIP on LIFE funding, including measures such as ditch cleaning, wetland restoration and leaving ditches untreated. The measures are being followed up through monitoring of water quality and water flows. The aim is to contribute knowledge so that the right measure is implemented in the right place.

Since the start of GRIP on LIFE’s monitoring and research at Trollberget in 2018, a large number of external research projects have joined the experimental site to increase knowledge, particularly regarding the effects of ditch-related measures. Studies in the area include the impacts of the measures on greenhouse gases, mercury, vegetation and water flows.

A comprehensive report from GRIP on LIFE on the research conducted at Trollberget will be presented at the end of this year. In addition, the project will compile a synthesis of the effects of wetland measures. The synthesis will also be presented at the end of the year.

Watercourses

Promoting habitats for animals and plants in and along watercourses is a focus area in GRIP on LIFE’s work. As with wetlands, some physical restoration of watercourses has been carried out within the project, but physical measures have not primarily been the project’s main activity. Instead, GRIP on LIFE has conducted various field inventories and mapping activities ahead of watercourse restorations. According to GRIP on LIFE, analyses of the current situation are an important prerequisite for understanding what needs to be addressed, and for being able, in the long term, to compare conditions before and after a measure.

One such example is the biotope inventories conducted by GRIP on LIFE in southwestern Sweden, which have provided central input into the development of the aforementioned Integrated Water Action Plan.

Knowledge about how machine-based stream restoration should be carried out varies considerably—even among those who are practically responsible for implementing the measures. This insight led GRIP on LIFE, together with the EU project Rivers of Life, to develop an online training platform (website) for the restoration of boulder-rich watercourses. The target group includes people who already work with, or are about to start working with, restoration—such as machine operators and planners. The platform is divided into two parts: a training module and a field support module. The platform was launched in spring 2025, and the response has been positive.

GRIP on LIFE has also carried out field sampling of watercourses at several sites in Sweden using eDNA technology, in which water samples are analysed to detect a particular species through DNA traces, without the need for direct observation. In GRIP on LIFE’s case, the focus has been on detecting the presence of freshwater pearl mussels. The conclusion is that eDNA technology is not a completely reliable method. The method has confirmed the presence of freshwater pearl mussels at certain sites where field inventories were also conducted. However, one cannot rule out that freshwater pearl mussels may still exist at other sampling points, since DNA degrades fairly quickly in aquatic environments. Nonetheless, the method can be useful in sensitive watercourses that are difficult to study using traditional methods.

Another field method that GRIP on LIFE has used in watercourses is electrofishing. This is a form of sampling where electric current is used to stun and catch fish in running waters. Before the fish are released back, they are weighed and measured. In this way, it is possible to gain an understanding of the fish population in the given watercourse. GRIP on LIFE has conducted electrofishing in various parts of the country, with a particular focus on trout in one of the large northern Swedish rivers and its tributaries. Valuable data on the current fish population in the river has been collected over many years.

Environmental considerations in forestry

Good environmental consideration during forestry operations is extremely important and is an issue that GRIP on LIFE addresses in various ways. Among other activities, the project has established approximately 70 demonstration areas with interpretive trails, where visitors can learn about forestry practices that consider water and the surrounding biodiversity. These demonstration areas—which are used in conjunction with meetings for forest owners and other stakeholders—are a central part of GRIP on LIFE’s efforts to disseminate knowledge about environmental considerations in forestry.

The demonstration areas are also open to those who wish to visit independently and access the information.

Environmental considerations in connection with forestry near lakes and watercourses often involve preserving the riparian buffer zone. And with good reason! A tree-covered buffer zone is of great importance for many species both in and along the water, as well as for water quality. One key question, both for research and for practical forestry, is how a buffer zone should be designed to function effectively—for example, providing shade, preventing erosion and water turbidity, and supplying food for aquatic species. GRIP on LIFE has contributed knowledge in this area by developing a basis for environmental assessment of buffer zones using GIS analyses.

Specifically, GRIP on LIFE carried out a GIS-based analysis of existing buffer zones in a particular watercourse in southern Sweden. In the relevant catchment area, the project is working to create better conditions for freshwater pearl mussels. The analysis of the watercourse’s buffer zones was conducted to improve understanding of their function and status. Various GIS platforms were used, and the analysis was primarily based on open data sources. The results include vector and raster data, statistics and tables.

GRIP on LIFE notes that the choice of method for mapping a watercourse is critical for obtaining accurate information about buffer zones. In this case, a hydrological model based on elevation data was used. Using this model, flow accumulation and flow lines were generated, which were subsequently used in the mapping of so-called DRIPs (discrete riparian inflow points). The analysis also includes a description of how shading in the buffer zones can be assessed using tree-height or canopy-cover rasters, as well as calculations of solar radiation. Shading is important for a range of species and their habitats.

In summary, the analysis provided a thorough understanding of the buffer zones in question, but above all, the methodology itself can serve as a model.

Specialists at SLU Swedish Species Information Centre, on assignment from GRIP on LIFE, made a unique compilation of knowledge about the rare alluvial forests with alder and ash (habitat type 91E0, hereafter referred to as alluvial forests) and riparian mixed forests of broadleaved species along major rivers (habitat type 91F0, hereafter referred to as riparian mixed forests), as well as concrete advice on the management and development of these habitat types. These types of forests grow along a watercourse and are regularly flooded. They are important biological hotspots for many species. Exactly how much of such forest there is in Sweden is uncertain, but studies indicate that there are only about 7000 hectares of alluvial forests and riparian mixed forests. Many of these are eking out a meagre existence. This is because a majority of Sweden’s large and medium-sized watercourses have been cleared, deepened, and straightened due to timber floating, and/or regulated for hydropower. This has resulted in many alluvial forests and riparian mixed forests disappearing, or, nowadays, being flooded to a degree too small to sustain them.

After reviewing the available knowledge, the SLU Swedish Species Information Centre has put forward several recommendations for the management of alluvial forests. One conclusion is that alluvial forests need about 25 days of continuous flooding at their ‘highest elevation level’ on the floodplain and preferably in the spring, every other or every third year.

Collaboration

Collaboration between different stakeholders is often a key factor in enabling measures affecting watercourses to be implemented. Multiple actors and interests are usually involved, and each may have a particular priority regarding how water and the surrounding land should be used. Frequently, these interests are conflicting.

This was the case in the catchment areas of two rivers in southern Sweden. Here, however, GRIP on LIFE had the opportunity to undertake an extensive, multi-year collaborative process with relevant stakeholders, including landowners, municipalities, environmental organisations and angling clubs. The goal was to reach consensus on a long-term plan to ensure sustainable development for both rivers. More specifically, this involved improving water quality, ensuring sustainable water use, promoting ecological restoration and enhancing biological diversity.

In December 2024, after five years of work, the plan could be presented. It contains both strategies and concrete activity plans for various measures. Two organisations were appointed to manage the work over the long term, and a number of individuals will continue to be involved after GRIP on LIFE concludes.

The collaboration process was carried out according to the established Conservation Standards methodology, a highly methodical approach designed to advance a process under the guidance of trained coaches. Over the years, many meetings and workshops were conducted with the participants. Some of the success factors identified in the process evaluation include engaged participants, a process structure that supports collective learning and co-creation, and the development of a team-building atmosphere. The process also allowed participants to highlight differences and discuss challenges. The fact that the process was led by trained facilitators was another critical factor, and not least, that the entire process was funded through GRIP on LIFE (i.e. the EU). A process of this kind requires substantial time and resources.

Collaboration—though in a very different form—has also been carried out in eastern Sweden with the state-owned forestry company Sveaskog and the energy company Mälarenergi. Within the framework of GRIP on LIFE, both companies signed separate agreements to work towards a favourable conservation status for freshwater pearl mussels in a specific catchment area. Here, GRIP on LIFE implements measures to support the population of this rare and threatened species. Each year, decisions are made about which measures will be implemented that year. In November, the year is evaluated and planning for the following year begins. The fact that the list of activities is renewed annually means that the agreement is not at risk of being filed away and forgotten.

GRIP on LIFE has also continued to work with and evaluate the use of so-called water management agreements developed by one of GRIP on LIFE’s partners in cooperation with Sveaskog. These agreements protect the forest immediately adjacent to particularly valuable watercourses for a period of 50 years. Forests near water are critically important for water quality and for the plant and animal life in and around the water. The agreement is signed by the landowner and the state, in this case, a county administrative board. It differs from most other nature conservation agreements in that it is concluded without any requirement for compensation.

One conclusion is that water management agreements can provide a rapid and effective form of protection. Generally, area protection is a long process that often involves many landowners, which can make it complicated to gain broad participation. However, by selecting a large landowner with property along a long stretch of the watercourse, the work is considerably facilitated. Within GRIP on LIFE, efforts have also been made to disseminate the working method more broadly. The project has also focused on individual private landowners in a limited geographic area to encourage them to sign water management agreements.

School and education

Since GRIP on LIFE is a knowledge-enhancing project, it has worked extensively with educational initiatives, ranging from preschool to university. Educational materials and training days have been two major efforts. Children and young people are often interested in nature: from an early age, it is important to communicate the significance of forests and water, and to explain ecological relationships in a simple, accessible way.

For the very youngest, the book Lump Wishes for an Adventure has been produced. Lump is a stone in the middle of a stream who dreams of exploring the wider world. In the book, children are invited to discover life in and around the stream. The book has been distributed free of charge to preschools, schools and libraries across the country and can now be found in every municipality in Sweden. In addition, it is available as an e-book, free for everyone. The book has become both well-received and popular, due in part to the strategic dissemination efforts that ensured it reached its intended audiences.

The teacher’s guide The Forest and the Water combines factual information about forests, forestry and water with suggestions for lessons and practical outdoor exercises. The material can be used for children aged 6–16, with lessons and activities adapted to different age groups. The Forest and the Water is primarily a digital publication, but a limited printed edition has been distributed to schools around the country. Interest in the material has been considerable, in part because GRIP on LIFE has also invested in inspiring teachers to use the book in their teaching, by organising outdoor training days and producing instructional films demonstrating how the material can be applied in practice.

At Sweden’s upper secondary agricultural schools, young people are trained for future careers in the forest sector, for example, as forest machine operators. GRIP on LIFE has organised annual training days on forestry and water for students at several of these schools, often held at one of the project’s demonstration sites. The training days have included information on, among other things, the ecosystem services provided by water, riparian buffer zones, ecological relationships, and the ways in which plants and animals in and around water can be negatively affected by human activities. The training days have been much appreciated, and to ensure continuation after the end of the project, GRIP on LIFE chose to produce the teacher’s guide, Forestry with Consideration for Water. This book compiles the knowledge shared during the training days, enabling teachers to continue delivering this instruction themselves.

Since the project began, efforts have also been made to disseminate knowledge about forestry and water considerations to university students enrolled in forestry-related programmes. During full-day field courses, theory has been combined with practical exercises, giving students the opportunity to learn about forestry near water, aquatic ecology and the restoration of aquatic environments. One conclusion is that it is particularly valuable to discuss these issues in the field, as it makes the learning more ‘hands-on.’

By spreading knowledge among children, young people and students, GRIP on LIFE helps ensure that the next generation enters adulthood with greater awareness of and interest in forests, nature and water—thereby helping to secure the future of streams, rivers, lakes and wetlands across the country.

Project facts

| Project Acronym | GRIP on LIFE-IP

|

| Project Title | Using functional water & wetland ecosystems and their services as a model for improving green infrastructure and implementing PAF in Sweden

|

| Funding | LIFE Programme

|

| Grant agreement | LIFE16IPE SE009

|

| Topic | Green Infrastructure/ Freshwater

|

| Total project budget | 16 653 702 €

|

| EU contribution | 9 693 702 € (58% of total eligible budget)

|

| Start and end date | 17/10/2017 – 31/07/2026

|

| Duration | 105 months

|

| Project Coordinator | Swedish Forest Agency

|

| Project Partners | Swedish Forest Agency,

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, County Administrative Boards of Västerbotten, Jämtland, Västmanland, Jönköping, Kalmar, Blekinge, and Halland, The Wetland Foundation, Ume/Vindel River Fishery Advisory Board, Baltic Sea Water District Authority, Swedish Forest Associations Södra Skogsägarna, Mellanskog, and Norra Skog.

|

| Project Locations | Sweden

|

For more information

Visit our website: www.life-remembrance.eu

Project summary

In GRIP on LIFE IP, public authorities in Sweden work together with forest owners’ associations, non-governmental organisations and researchers to improve environmental consideration to waters and wetlands in the forest landscape, while continuing an active forest management. Our goal is to improve the environment and conditions for animals and plants living in the forest’s watercourses and wetlands.

Project lead profile

Lead partner is the Swedish Forest Agency, the national authority responsible for forest-related issues. Its main function is to promote the management of Sweden’s forests to meet forest policy goals. The forest policy places equal emphasis on two main objectives: production goals and environmental goals. The agency cooperates with forest industries and the environmental sector.

Project contacts

Project Manager: Gunilla Oleskog

Email: gunilla.oleskog@skogsstyrelsen.se

Web: www.griponlife.se

Instagram: @griponlifeip

Facebook: @griponlifeip

YouTube: @griponlifeip

Funding

The GRIP on LIFE IP project has received funding from the LIFE programme of the European Union under grant agreement No. LIFE16 IPE/SE/009 GRIP.

Figure legends

A restored wetland in southernmost Sweden, where inventories showed a marked increase in the number of species in the years following restoration. Photo: Bitzer Productions.

GRIP on LIFE staff plan a wetland restoration together with the landowner. Photo: Richard Lindor.

Next to a stream, GRIP on LIFE has created a wetland and floodplain. By raising the stream bed, water can regularly flood the area, establishing important habitats for animals and plants. Photo: Richard Lindor.

Tadpoles in a wetland. Amphibians benefit from wetland restoration and are able to establish themselves quickly after restoration. Photo: Bitzer Productions.

The fish population in a stream in northern Sweden is surveyed using electrofishing. Photo: Lena Allthin.

View of part of the Trollberget Experimental Area. Greenhouse gas measurement equipment can be seen in the distance. Photo: Lena Allthin.

Greenhouse gas fluxes are measured at a restored mire and compared with fluxes from a pristine mire. Photo: Bitzer Productions.

Part of the Lyckeby River in southernmost Sweden, one of the areas where GRIP on LIFE has been active. Photo: Leif Gustavsson

The books ‘The Forest and the Water’ and ‘Lump Wishes for an Adventure’, created for children by GRIP on LIFE.