Josep Torrellas and Jovan Stojkovic

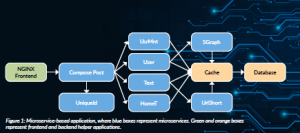

Cloud computing is undergoing a paradigm shift. Large monolithic applications are being replaced by compositions of many lightweight, loosely-coupled microservices (Richardson, 2023). Each microservice is built and deployed as a separate program that executes part of the application’s functionality, such as key-value serving, protocol routing or ad serving. Figure 1 shows an example of a microservice-based application.

This approach simplifies application development, as it enables the composition of heterogeneous modules of different programming languages and frameworks. Moreover, each microservice can be shared among multiple applications while being scaled independently.

As a result, this paradigm is supported by major IT companies such as Amazon, Netflix, Alibaba, Twitter, Uber, Facebook and Google. In addition, there are many open-source systems that manage microservices, such as Kubernetes and Docker Compose.

Building on the microservices model, the next evolution of cloud computing is serverless or function-as-a-service (FaaS) (Amazon Web Services, 2025). It retains the modular structure of microservices and simplifies their deployment and management. Specifically, applications are composed of a set of functions. Developers do not provision or manage the infrastructure for each function. They simply upload the functions, and the cloud provider handles the runtime environment, system services and scaling. Each function runs in an ephemeral, stateless container or micro virtual machine that is created and scheduled on demand in an event-driven manner. In this environment, applications can achieve high resource utilisation, scale seamlessly and benefit from fine-grained billing. Today, serverless computing is offered by all major cloud providers and is widely used in domains such as e-commerce, image and video processing, and machine learning inference and training.

The combination of microservice and serverless environments is often called ‘cloud-native’. This article examines what makes cloud-native environments hard to support and the techniques that the ACE Center for Evolvable Computing (ACE, 2025) has designed to execute them efficiently.

What makes these workloads hard to support?

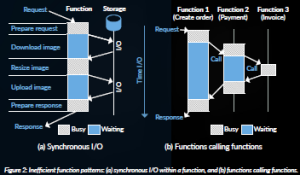

Cloud-native workloads are hard to support efficiently in distributed systems with conventional servers and conventional software stacks. The reason is that they differ from traditional monolithic applications. Indeed, the typical execution time of a service (i.e. a microservice or a FaaS function) is of the order of only a millisecond. Further, the CPU core is often stalled, waiting for responses to I/O operations to global storage or for the return of a callee service running on another node. This is shown in Figure 2. During the stall time, the CPU core may choose to context switch, in which case, the cache is polluted by other services.

Other important characteristics of these workloads are that services often exhibit bursty invocation patterns and that they have stringent tail-latency bounds, requiring most of the requests (e.g. 99%) to complete within a strict deadline. These characteristics have important implications, as we will see.

Rethinking the CPU hardware

Current CPUs are not a good match for cloud-native environments, as shown in Table 1.

First, conventional processors have powerful cores, with extensive hardware for instruction level parallelism (ILP) and large caches; cloud-native environments execute many small-sized services that have frequent branches, I/O invocations, and other system calls that inhibit ILP. Further, conventional multicores invest significant hardware and design complexity to support global hardware cache coherence; services hardly share writable data through memory. Inaddition, conventional processors incorporate microarchitectural mechanisms for long-running, predictable applications, such as advanced prefetchers and branch predictors; cloud-native environments execute short-running services, and frequently interrupt them with context switches. Finally, while current processors are optimised to minimise the average latency of programs, the key performance target in cloud-native environments is minimising tail latency of service requests (e.g. improving the 99th-percentile responses).

Table 1: Mismatch between current processors and cloud-native environments.

| Current processors | Cloud-native environments |

| Powerful cores and large caches | Small-sized services; low ILP |

| Global hardware cache coherence | No writable data sharing |

| Optimised for long-running, predictable applications | Short-running services; frequent context switching |

| Maximise average performance | Strict tail latency requirements |

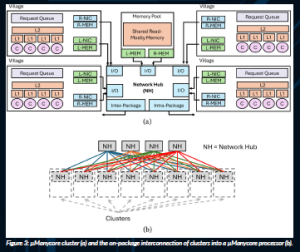

This new environment calls for a new processor design that we call µManycore (Stojkovic et al., 2023a). A µManycore has many simple cores rather than a few large cores. It does not support global hardware cache coherence. Instead, it has multiple small hardware cache-coherent domains of 4–16 cores called villages. In a village, services can communicate using shared memory, while across villages they use network messages. Groups of villages form a cluster (Figure 3a), and multiple clusters form the processor. Most importantly, the µManycore design is comprehensively optimised for tail-latency reduction. This means that, in addition to targeting inefficiencies affecting all service requests, the design allocates special hardware to smooth out contention-based overheads that may affect a subset of requests.

Table 2 shows the main sources of tail latency and how µManycore handles them. µManycore includes hardware supported enqueuing, dequeuing and scheduling of service requests, as well as context switching. In addition, since contention in the on-package network is a major source of tail latency, µManycore interconnects its clusters in a hierarchical leaf-spine network topology (Figure 3b). Such a network has many redundant, low-hop-count paths between any two source and destination clusters. Hence, multiple messages can proceed in parallel from the same source to the same destination cluster without delaying one another.

Table 2: Main sources of tail latency in a cloud-native CPU.

| Source | Reason | µManycore solution |

| Request scheduling | Synchronisation and queuing of requests | Request enqueuing, dequeuing and scheduling in hardware |

| Context switching | OS invocation and state saving and restoring | Hardware-based context switching |

| On-package network | Network link/router contention | On-package hierarchical leaf-spine network |

Harvesting hardware

In cloud-native environments, users allocate a virtual machine (VM) or a container (i.e. an instance) with a specified number of cores and amount of memory to serve invocations (i.e. requests) for a given service. However, the requests for a service exhibit bursty patterns. Hence, to attain good performance at all times, users typically provision instances for peak loads. As a result, cloud-native environments exhibit low core utilisation for most of the time.

To combat resource underuse in general workloads, Microsoft has introduced Harvest VMs. In a system, there are two types of VMs: Primary and Harvest VMs. Primary VMs run latency-critical applications, expect high performance, and are created with a specified number of cores; Harvest VMs run batch applications, have loose performance requirements and can tolerate resource fluctuations. Harvest VMs dynamically grow by harvesting temporarily idle cores owned by a Primary VM. When the Primary VM needs its cores, it reclaims them back. This technique can substantially increase core utilisation.

Sadly, re-assigning a core from one VM to another is costly. The overheads include hypervisor calls to detach the core from one VM and attach it to another VM, an expensive cross-VM context switch, and the flush and invalidation of the re-assigned core’s private caches and TLBs. The latter is needed to eliminate a potential source of information leakage. We find that the sum of all these overheads can easily exceed 5 ms. Such overhead is tolerable when Primary VMs run long monolithic applications. However, it is not acceptable in cloud-native environments where an incoming 1-ms service request for a Primary VM needs to wait several ms to reclaim a core.

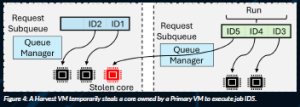

To enable core harvesting in cloud-native environments, we support it in hardware. Specifically, we augment µManycore with the HardHarvest extensions (Stojkovic, 2025b), which target the two main overheads of conventional software-based core harvesting. The first overhead is core re-assignment. To minimise it, HardHarvest organises the hardware request queue into per-service subqueues. A core is re-assigned from a Primary VM to a Harvesting VM by being allowed to dequeue requests from the new VM’s subqueue when the original subqueue is empty (Figure 4). Similarly, when a new request for a Primary VM arrives, a loaned core is interrupted and forced to dequeue from the original subqueue. There are no detach/attach system calls.

The second overhead is flushing and invalidating private caches and TLBs on core re-assignment. To reduce it, HardHarvest leverages the fact that services typically have small working sets. Specifically, HardHarvest partitions these structures into two regions: Harvest and non-Harvest. When a core executes a Primary VM, it can use both

regions; when it executes a Harvest VM, it can only use the Harvest region. When a core transitions between VMs, only the Harvest region is flushed and invalidated; the non-Harvest region preserves the Primary VM’s state during the core loan. With HardHarvest, cores attain high utilisation, the tail latency of Primary VM requests suffers minimal or no increase, and the throughput of Harvest VMs workloads increases substantially.

Costly storage accesses

For high availability and fast scalability, services in a cloud-native environment are commonly implemented as stateless. This means that all the data of a service is discarded from a node once the service is unloaded from the node; any durable

data must be stored in global storage. This results in inefficient data reuse, as subsequent service invocations must reload their data from global storage. Further, for scalability and security reasons, any communication between services must occur through the global storage. All these costly accesses to global storage hurt the performance of services.

To mitigate this cost, data can be cached locally in the memory of the nodes where services execute.

However, distributed software caches add a new challenge to the cloud-native infrastructure: how to keep these caches coherent. Unfortunately, current schemes address this challenge in suboptimal ways for cloud-native environments. Specifically, most schemes cache a data item in the memory of only a single node, called the item’s home node. As a result, a service invocation running on a node frequently issues accesses to other nodes to get data items from their homes.

An exception is Faa$T (Romero et al., 2021), which allows a data item to be cached in multiple nodes and uses a versioning software protocol to keep caches coherent. It associates a version number with each data item. Data items have a home node, which caches the latest data value and version number. When a non-home node reads the data item, it first fetches the item’s version number from the home, even if it caches the data item locally. Then, it compares the version number in the home with the locally cached version number. If the two numbers match, the service accesses the data item directly from the local cache. Otherwise, it fetches it from the home.

This protocol works well for relatively large data items, where fetching only the small version number is much cheaper than fetching the entire data item. However, it is suboptimal in cloud-native environments, where most storage accesses are reads to small data items. In this case, the time to fetch the version number is comparable to the time to fetch the data item, and most version comparisons are unnecessary, as writes are rare.

To attain high performance in cloud-native settings, we use a new distributed cache-coherence software protocol based on invalidations. We call it Concord (Stojkovic et al., 2025a). Invalidation-based protocols, though common in hardware systems, have been disregarded in distributed software environments. The reasons are that coherence directories introduce fault-tolerance concerns and that invalidation messages may scale poorly with increasing numbers of nodes. However, invalidation-based protocols can be a good match for cloud-native environments. The reasons are that services are stateless and therefore easier to recover from failures, and that the low frequency of writes keeps invalidation traffic low.

In Concord, each application is assigned a software data cache distributed across the memories of the nodes where the application runs. To make the protocol more resilient to failures, Concord employs write-through caching. When a node crashes, a coordination service redistributes the data items homed in the crashed node. Overall, Concord achieves high performance while enhancing fault tolerance.

Speculative execution

Cloud-native applications are composed of multiple services chained together. Hence, rather than speeding up individual services, we now consider accelerating whole application workflows. To understand how we can do so, consider a smart home FaaS application composed

of seven functions (Figure 5a). The Login function may return true or false. If the former, multiple functions in sequence read the temperature, normalise it and compare it to a threshold. Based on the comparison, the air conditioner may be turned on. The workflow is shown with condition outcomes and the data that is passed between functions. We can see that there are cross-function control and data dependencies.

In many applications, we find that the outcomes of the branches that encode cross-function control dependences are fairly predictable. Further, since functions are typically stateless, they often produce the same output every time that they are invoked with the same input. Hence, we also find that the cross-function data dependences are predictable.

With these insights, we propose to accelerate cloud-native applications using software-supported speculation. With this approach, called SpecFaaS (Stojkovic et al., 2023b), the functions of an application are executed early, speculatively, before their control and data dependences are resolved. Control dependences are predicted with a software-based branch predictor like those in processors. Data dependences are predicted with memoization, i.e., by maintaining a table of past input-output pairs observed for the same function. With this support, the execution of downstream functions is overlapped with that of upstream functions, substantially reducing the end-to-end execution time of applications. Figure 5b shows the timeline of the example application under conventional execution in the common case when both branches are true. Figures 5c and d show the timelines when using speculative execution of only control and of both control and data, respectively.

While a function execution is speculative, SpecFaaS prevents its buffered outputs from being evicted to global storage. When the dependences are resolved, SpecFaaS proceeds to validate the function. If no dependence has been violated, the function commits. Otherwise, the buffered speculative data is discarded, and the offending functions are squashed and re-executed.

Concluding remarks

The nascent cloud-native environments offer many opportunities for improvement. For example, it is known that cloud-native services suffer from the execution of auxiliary operations known as datacentre tax. They include operations such as data compression, data encryption, and transmission control protocol (TCP). These operations can be sped up with hardware accelerators. Another area of research is how to reduce the rising energy consumption and carbon footprint of these environments. This problem can be studied in the context of many heterogeneous accelerators and a mix of renewable and non-renewable energy sources.

References

ACE (2025) The ACE Center for Evolvable Computing. Available at: https://acecenter.grainger.illinois.edu (Accessed: 27 October 2025).

Amazon Web Services (2025) AWS Lambda. Available at: https://aws.amazon.com/lambda/. Richardson, C. (2023) What are microservices? Available at: https://microservices.io/.

Romero, F., Chaudhry, G.I., Goiri, I., Gopa, P., Batum, P., Yadwadkar, N., Fonseca, R., Kozyrakis, C. and Bianchini, R. (2021) ‘Faa$T: A transparent auto-scaling cache for serverless applications’, Proceedings of the 12th ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing (SoCC ’21).

Stojkovic, J., Liu, C., Shahbaz, M. and Torrellas, J. (2023a) ‘µManycore: A cloud-native CPU for tail at scale’, Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA ’23).

Stojkovic, J., Xu, T., Franke, H. and Torrellas, J. (2023b) ‘SpecFaaS: Accelerating serverless applications with speculative function execution’, Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA ’23).

Stojkovic, J., Alverti, C., Andrade, A., Iliakopoulou, N., Xu, T., Franke, H. and Torrellas, J. (2025a) ‘Concord: Rethinking distributed coherence for software caches in serverless environments’, Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA ’25).

Stojkovic, J., Liu, C., Shahbaz, M. and Torrellas, J. (2025b) ‘HardHarvest: Hardware-supported core harvesting for microservices’, Proceedings of the 52nd Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA ’25).

Project summary

The aim of the ACE Center is to devise novel computing technologies that will substantially improve the performance and the energy efficiency of distributed computing. ACE innovates in processing, storage, communication, and security technologies that address the seismic shifts identified in the Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC) Decadal Plan for Semiconductors.

Project partners

The ACE team is: Josep Torrellas (Director, Univ. Illinois), Minlan Yu (Assistant Director, Harvard), Tarek Abdelzaher (Univ. Illinois), Mohammad Alian (Cornell), Adam Belay (MIT), Rajesh Gupta (UCSD), Christos Kozyrakis (Stanford), Tushar Krishna (GaTech), Arvind Krishnamurthy (Univ. Washington), Jose Martinez (Cornell), Charith Mendis (Univ. Illinois), Subhasish Mitra (Stanford), Muhammad Shahbaz (Univ. Michigan), Rachee Singh (Cornell), Steven Swanson (UCSD), Michael Taylor (Univ. Washington), Radu Teodorescu (Ohio State Univ.), Mohit Tiwari (Univ. Texas), Mengjia Yan (MIT), Zhengya Zhang (Univ. Michigan) and Zhiru Zhang (Cornell).

Project lead profile

Josep Torrellas is a Professor of Computer Science at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His research interests are parallel computer architectures. He has contributed to experimental multiprocessors such as IBM’s PERCS Multiprocessor, Intel’s Runnemede Extreme-Scale Multiprocessor, Illinois Cedar and Stanford DASH. He is a Fellow of IEEE, ACM, and AAAS. He received a PhD from Stanford University.

Jovan Stojkovic is a recent PhD graduate from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He will start as an Assistant Professor of Computer Science at the University of Texas at Austin.

Project contacts

Josep Torrellas

201 N. Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, IL, 61801, USA.

Email: torrella@illinois.edu

Web: https://acecenter.grainger.Illinois.edu

https://iacoma.cs.uiuc.edu/josep/torrellas.html

Funding

This work was supported by the Joint University Microelectronics Programme (JUMP 2.0) sponsored by the Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Figure legends

Figure 1: Microservice-based application, where blue boxes represent microservices. Green and orange boxes represent frontend and backend helper applications.

Figure 2: Inefficient function patterns: (a) synchronous I/O within a function, and (b) functions calling functions.

Figure 3: µManycore cluster (a) and the on-package interconnection of clusters into a µManycore processor (b).

Figure 4: A Harvest VM temporarily steals a core owned by a Primary VM to execute job ID5.

Figure 5: Execution of a smart home FaaS application.