Andrea Gonzalez-Montoro, Instituto de Instrumentación para Imagen Molecular (i3M),

Centro Mixto CSIC – Universitat Politècnica de València

Molecular imaging (MI) techniques focus on visualising and quantifying biological processes at the cellular and molecular level within living organisms. This information allows for early diagnoses, personalised treatment plans and a deep understanding of some medical conditions (Pysz, Gambhir and Willmann, 2010).

There are different MI techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), optical imaging and ultrasound. Yet, despite achieving submillimetre spatial resolution, these techniques report low sensitivity. Complementary nuclear (or molecular) medicine imaging techniques report much higher sensitivity but require the use of ionising radiation, such as single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) (Cherry, Sorenson and Phelps, 2012). Among the molecular imaging techniques, PET imaging constitutes the modality of excellence for detecting and quantifying small amounts of exogenously administered radiotracers. These radiotracers are synthetic derivatives of a molecule in which one or more atoms have been replaced by a radioactive one (Phelps, 2004). One of the most used radiotracers in PET imaging is [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), in which a glucose molecule is combined with 18F.

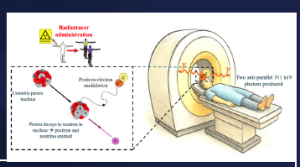

The PET imaging process starts with the injection of these radiotracers, which circulate along the bloodstream and accumulate in the areas of interest (i.e. areas of high metabolic activity, such as tumours, brain, prostate, etc.). The radioisotope decays, emitting a positron that annihilates with a surrounding electron in the patient’s body. As a result, two 511 keV gamma rays are emitted in opposite directions (180±0.5°) and escape from the body. These two annihilation photons interact with two opposite PET detectors and, if they are collected within a defined time window (usually in the nanosecond (ns) range), are stored as a coincidence event. Finally, the events are sent to a PC where software methods are applied for photon impact positioning, calibration and image reconstruction. Note that the performance of the scanners depends on the convolution of the aforementioned processes, but the main factor affecting detection performance is the PET detector block (Townsend, 2004). See Figure 1 for an example of this process.

Conventional PET scanners are widely used in oncology for the diagnosis and staging of many diseases, as well as in neurology, urology and cardiology. Moreover, PET imaging has been demonstrated to play an important role, not only in adult patients but also in children. For example, PET improves diagnostics for many paediatric cancers, such as leukaemias, lymphomas and the associated organs (Zhuang and Alavi, 2020). Nevertheless, despite being the MI technique of choice in most cases, state-of-the-art whole body (WB)-PET scanners are not optimised for precise imaging of paediatric patients.

The use of clinical PET in paediatrics is compromised by several factors such as: reduced axial field of view (FOV) which makes almost impossible to image the entire child body in one acquisition; insufficient spatial resolution, clinical WB-PET reports 3–5 mm at the centre, significantly degrading towards the edges of the FOV, which is inadequate for visualising small lesions; and low effective sensitivity, the reduced axial coverage limits the collection of count to only 1% which imposes injecting high doses of radiotracers. This is life-threatening for children, as they are more sensitive to the effects of radiation than adults and have longer post-exposure life expectancy in which to exhibit adverse radiation effects. Also, since scanning times are long, the patient has to be sedated, imposing an additional risk for children due to the potential neurotoxicity related to the need for general anaesthesia (Roberts and Shulkin, 2004).

To overcome these limitations, PET research in paediatrics has been focused on reducing patient dose and sedation whenever possible, while keeping good image quality and diagnostic performance. To do so, it is mandatory to boost the effective sensitivity of the scanner and, so far, there are three main paths to enhance sensitivity (Gonzalez-Montoro and Gonzalez, 2022):

- Extending the axial length of the scanner (total body (TB)-PET) is necessary as paediatric solid tumours may metastasise, requiring children to be assessed for disease in different parts of their body. Yet, building such large systems imposes major technological challenges, higher production costs, and complex hardware, making their transference to hospitals or research centres complicated.

- Including photon time-of-flight (TOF) information during the image reconstruction process to enhance signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

- Placing the detectors closer to the area under study to enable higher sensitivity at lower cost. But multi-organ studies are not possible since they cover small areas of the body.

The present European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant (PHOENIX) focuses on advancing current paediatric PET imaging by simultaneously meeting the three previously described options. The project, called PHOENIX, will be devoted to achieving ultra-high sensitivity and extending the use of PET in paediatrics.

PHOENIX aims to reach such a high sensitivity by:

- Using thick detectors, extending the axial length to 54.5 cm and placing the detectors as close as possible to the area under study (bore diameter ~32 mm, based on average child size), see Figure 2. The expected geometrical sensitivity increase is (x10, simulated) compared to a 24 cm long scanner.

- Enabling TOF capabilities by exploiting the scintillator Cherenkov’s yield of Bismuth Germanate (BGO) scintillators (Gonzalez-Montoro et al., 2022). Since Cherenkov photons are prompt-emitted light, they are key to unlocking precise estimation of the TOF kernel during reconstruction. PHOENIX targets a coincidence time resolution (CTR) value of 350 ps, which will result in a TOFsensitivity gain of x2.5–3.

The resulting total effective sensitivity (geometrical x TOF) gain will allow performance to be pushed towards better effective sensitivity (x30) than the one reported by the state-of-the-art scanners. Also, PHOENIX aims to provide—for the first time in TB-PET imaging—a uniform spatial resolution of 2–3 mm across the entire FOV of the scanner by including 3D photon positioning capabilities, thus mitigating the radial-dependent degradation of the spatial resolution and the blurring effect in the reconstructed image.

A major achievement of the PHOENIX project (which will provide a prototype version of the real scanner) will be the development of novel readout and frontend electronics in a scalable format. For the best trade-off between 3D position capabilities, TOF performance and cost, the PHOENIX detector will be based on BGO semi-monolithic (slabs (Cucarella et al., 2021)) scintillators, see Figure 2 (left). If successful, this BGO-based PET detector will surpass state-of-the-art technology and will be used to build the scanner, making it possible to fully exploit paediatric TB-PET imaging.

The development of PHOENIX will allow for:

- low-dose imaging by exams to facilitate paediatric imaging due to its homogeneous spatial resolution and high effective sensitivity (x30). These features will enable reduced injected doses, shorter scan times, or a combination of both.

- improved diagnostics at low cost using affordable custom-designed technology and scintillators, without compromising performance. Indeed, the targeted resolution may enable visualising anatomic details (better understanding of the lesion) and improve studies of children’s diseases.

- new imaging protocols, with the option for screening and for extending PET to new patient categories. With the expected increase in sensitivity, one of the critical points limiting the extension of PET in paediatrics will be solved by surpassing state-of-the-art sensitivity values.

- dynamic and simultaneous studies of several organs for the comprehension of certain pathologies and for monitoring the effectiveness of the treatment. The extended FOV of the PHOENIX scanner will allow visualising all organs in a single FOV, enabling novel studies and interactions between organs.

- PET image of tumour heterogeneity. The unprecedented resolution in combination with the excellent image quality may allow for the detailed study of small lesions and tumoural structures.

The PHOENIX project has already started and is in the phase of selecting the detector components and validating the proof-of-concept electronic chain for event classification based on their dynamics (fast scintillation and ultrafast scintillation + Cherenkov).

If successful, the PHOENIX system will become a breakthrough in technology transfer, as it will provide a solution for constructing low-dose, high-sensitivity, affordable paediatric TB-PET scanners.

References

Cherry, S.R., Sorenson, J.A. and Phelps, M.E. (2012) Physics in Nuclear Medicine. 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Cucarella, N., Barrio, J., Lamprou, E., Valladares, C., Benlloch, J.M. and Gonzalez, A.J. (2021) ‘Timing evaluation of a PET detector block based on semi-monolithic LYSO crystals’, Medical Physics, 48, pp. 8010–8023. doi: 10.1002/mp.15318.

Gonzalez-Montoro, A. and Gonzalez, A.J. (2022) ‘A PET detector suitable for low-dose imaging’, 2022 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), Italy, 2022, pp. 1–3. doi: 10.1109/NSS/MIC44845.2022.10398991.

Gonzalez-Montoro, A., Pourashraf, S., Cates, J.W. and Levin, C.S. (2022) ‘Cherenkov radiation–based coincidence time resolution measurements in BGO scintillators’, Frontiers in Physics, 10. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.816384.

Phelps, M.E. (2004) PET: Molecular Imaging and Its Biological Applications. 1st edn. New York: Springer Nature.

Pysz, M.A., Gambhir, S.S. and Willmann, J.K. (2010) ‘Molecular imaging: current status and emerging strategies’, Clinical Radiology, 65(7), 500–516. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.03.011.

Roberts, E.G. and Shulkin, B.L. (2004) ‘Technical issues in performing PET studies in paediatric patients’, Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology, 32(1), pp. 5–11.

Townsend, D.W. (2004) ‘Physical principles and technology of clinical PET imaging’, Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 33(2), pp. 133–145.

Zhuang, H. and Alavi, A. (2020) ‘Evolving role of PET in paediatric disorders’, PET Clinics, 15(3), xv–xvii. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2020.05.001.

Project summary

Positron emission tomography (PET) constitutes the imaging modality of excellence in nuclear medicine. However, conventional PET scanners are not optimised in terms of sensitivity and spatial resolution. Moreover, since PET imaging requires injecting radiotracers, its use is compromised in paediatrics.

To extend the use of PET, I aim to develop a prototype version of a total body PET for paediatric imaging. The system, named PHOENIX, targets a sensitivity 30 times greater than that of clinical PET. The detectors will be based on semi-monolithic scintillators after BGO. This design allows characterising the light distributions to enable 3D photon interaction positioning while providing time-of-flight capabilities by exploiting the BGO´s Cherenkov yield. If successful, PHOENIX will promote PET imaging of children, improve its diagnostic capabilities, staging and response assessment.

Project lead profile

Andrea Gonzalez-Montoro, PhD in Physics. Her research focuses on developing novel PET instrumentation. She got her PhD from the University of Valencia (UV) in 2018, joined Stanford University as a Postdoctoral Fellow in 2019 and, in 2023, got a postdoctoral position at the Spanish Research Council (CSIC) and came back to i3M.

She is an organiser and lecturer for the IEEE NPSS/EduCom and is co-founder and president of the association Women of Science in Spain.

Project contacts

Andrea Gonzalez-Montoro

Instituto de Instrumentación para Imagen Molecular (I3M), Ciutat Politècnica de la Innovación, Edificio 8B, acceso N, planta 0. Camino de vera s/n, 46022, València, Spain.

Email: andrea.gm@i3m.upv.es

Web: https://i3m.csic.upv.es/research/stim/dmil/

LinkedIn: /in/andrea-gonzalez-montoro-81b81117a

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101164363).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: PET imaging process: the top panel shows the event acceptance scheme and an example of a human brain PET image; the bottom panel exemplifies the radiotracer injection and the positron-electron annihilation that results in the two 511 keV gamma rays detected by two detectors of the PET ring.

Figure 2: Schematics of (left) one PHOENIX detector unit showing the BGO slab-based scintillator, the photosensor matrix and the electronic board, and (right) PHOENIX paediatric PET system with non-scaled dimensions.