ERC project TAOC group:

Elian Vanderborght, Reyk Borner, Lucas Esclapez, Valérian Jacques-Dumas, Oliver Mehling, Emma Smolders, Jelle Soons, René M. van Westen and Henk A. Dijkstra (PI)

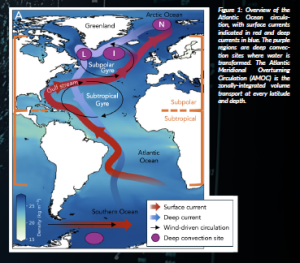

The Atlantic Ocean circulation plays a key role in the global climate by redistributing heat through the global ocean. This large-scale ocean circulation transports relatively warm surface waters northward. Combined with the prevailing eastward winds over the Atlantic Ocean, this explains the relatively mild climate over Western Europe compared to other regions at the same latitude (e.g. Canada). The warm surface currents flow further northward to Greenland, where they cool, sink, and then flow southward at greater depth (Figure 1). This conveyor belt of water is not only important for the global climate but also influences storm-track activity, large-scale precipitation patterns and regional sea levels.

Tipping of the Atlantic Ocean circulation

There is growing concern about the changes in the Atlantic Ocean circulation under future climate change, as it is considered a tipping element in the climate system. Tipping behaviour occurs when an initial perturbation is amplified by self-reinforcing feedback. The Atlantic Ocean circulation is already being perturbed by freshwater input from the melting Greenland Ice Sheet, a process expected to intensify in the future. This influx of freshwater lightens the surface waters of the North Atlantic, reducing the density-driven sinking that sustains the circulation. There may exist a critical threshold of freshwater input beyond which sinking ceases entirely, causing the Atlantic Ocean circulation to shift to a much weaker, fully collapsed or even reversed state. Such a transition would have major regional and global impacts, in addition to the effects of anthropogenic climate change. Climate model projections consistently indicate a weakening of the Atlantic Ocean circulation throughout the 21st century, and observation-based early warning indicators (Ditlevsen and Ditlevsen, 2023) suggest that an onset of such a collapse may be imminent.

The ERC-funded TAOC project (Tipping of the Atlantic Ocean Circulation, PI: H.A. Dijkstra) is focused on estimating the probability that the present-day Atlantic Ocean circulation will start to collapse before the end of the century. Within this project, a hierarchy of climate models is used, from conceptual climate models to modern complex climate models. The conceptual climate models help to understand the core dynamics and feedback mechanisms of tipping, and these models require only limited computational resources compared to the complex climate models.

Simulating tipping of the Atlantic Ocean circulation

A recent analysis (van Westen and Dijkstra, 2024) within the TAOC project shows that complex climate models have persistent biases. The largest model bias is that the Indian Ocean becomes too fresh, which is related to ocean-atmospheric feedbacks that are not well captured within such climate models. The Indian Ocean salinity bias eventually influences the salinity fields in the Atlantic Ocean. The strength of Atlantic Ocean circulation and the possibility of tipping are particularly sensitive to the Atlantic Ocean salinity content (Vanderborght, van Westen and Dijkstra, 2025). These persistent salinity biases likely explain why tipping in complex climate models has been difficult to find. One way to test this hypothesis is by correcting for model bias through a so-called ‘hosing experiment’, where extra fresh water is added to the North Atlantic in the model. If the freshwater input is gradually increased, the circulation may eventually tip. Increasing the freshwater flux slowly ensures that such a tipping event is generated by the ocean’s own internal feedbacks rather than by the forcing itself (Dijkstra and van Westen, 2025).

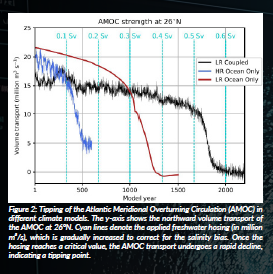

Within the TAOC project, several hosing simulations have now been carried out using global climate models of different complexity (Figure 2). These include a low-horizontal (about 100 km × 100 km) resolution ocean-only model (LR Ocean Only), a high-horizontal (about 10 km × 10 km), resolution ocean-only model (HR Ocean Only) and a low-horizontal (100 km x 100 km in the ocean and 200 x 200 km in the atmosphere) resolution climate model (LR Coupled). In all of these simulations (van Westen, Kliphuis and Dijkstra, 2024; 2025a), the Atlantic circulation was found to tip. This shows that correcting for model biases makes the circulation appear more vulnerable to collapse, helping to better understand its true stability. At the moment, a hosing simulation is performed with a high-resolution coupled climate model, which could provide even stronger evidence for Atlantic Ocean circulation tipping under more realistic, bias-corrected conditions.

Predicting the onset of tipping of the Atlantic Ocean circulation

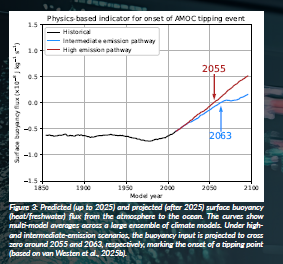

Of particular relevance to policymakers is an estimate of the probability that the Atlantic Ocean circulation could tip in the future. Obtaining such an estimate is challenging, not only because climate models are computationally expensive to run, but also because each model has its own biases and uncertainties, which reduce the reliability of any probability calculation. Within the TAOC project, building on hosing experiments and recent theoretical advances, we have identified (van Westen et al., 2025b) an indicator that measures the tendency of the atmosphere to make North Atlantic surface waters lighter or heavier. This indicator changes sign—from negative to positive—when the Atlantic Ocean circulation approaches a tipping point (Figure 3). It can be evaluated using a wide range of contemporary climate models and even observations, enabling a robust, physically based statistical estimate of tipping probability under different forcing scenarios. Results suggest that a tipping of the Atlantic circulation could start as early as 2055 (Figure 3)!

This research has attracted considerable media attention and sparked interest among European Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra, see https://www.linkedin.com/posts/wopke-hoekstra_part-of-my-job-as-commissioner-is-to-highlight-activity-7366762591274098689-7Jjd, who remarked: “There’s a sense out there that climate change has taken a backseat because we’re so busy dealing with other pressing concerns. I know young people are frustrated by this. I am, too, to a certain extent. But I’ve also been in politics long enough to know that progress takes time, that it’s not linear and that there’ll be moments when attention wanes. So a big thanks to these scientists for giving us another serious climate wake-up call.”

Importantly, although an intermediate-emission scenario delays the estimated multi-model mean tipping point by only eight years (Figure 3), results from the TAOC project showed that this estimate carries a higher degree of uncertainty than under the high-emission scenario. This indicates that lowering emissions can substantially reduce the likelihood of the circulation tipping.

Impacts

Recent work within the TAOC project has also used a complex coupled climate model to simulate a tipping of the Atlantic circulation under moderate-and high-emission scenarios. This makes it possible to assess climate impacts arising from the combined effects of Atlantic Ocean circulation tipping and ongoing global warming. A dashboard was made within the TAOC project to clearly show these impacts (see www.amocscenarios.org/) across different climate scenarios and for both cases: whether or not the Atlantic Ocean circulation is tipping. Such results are important for policymakers involved in designing adaptation scenarios due to such a tipping event (van Westen et al., 2025b).

In a moderate-emission scenario, Northwestern Europe is projected to cool when the Atlantic Ocean circulation tips, indicating that the tipping-induced cooling outweighs the influence of global warming. The effect is strongest in winter, when much colder conditions and enhanced storm-track activity are expected. In a high-emission scenario, by contrast, strong global warming largely offsets the cooling in Northwestern Europe. However, the loss of northward heat transport causes the Southern Hemisphere to warm disproportionately. In addition, shifts in the Atlantic circulation alter global precipitation patterns, leading to drier conditions in Northwestern Europe (van Westen and Baatsen, 2025).

References

Ditlevsen, P. and Ditlevsen, S. (2023) ‘Warning of a forthcoming collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation’, Nature Communications, 14(1), pp. 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39810-w.

Dijkstra, H.A. and Van Westen, R. (2025) ‘The probability of an AMOC collapse onset in the twenty-first century’, Annual Reviews Marine Science. Available at: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-marine-040324-024822.

van Westen, R. and Dijkstra, H.A. (2024) ‘Persistent climate model biases in the Atlantic Ocean’s freshwater transport’, Ocean Science, 20, pp. 549–567. doi: 10.5194/os-20-549-2024.

van Westen, R., Kliphuis, M. and Dijkstra, H.A. (2024) ‘Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course’, Science Advances, 10, eadk1189. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1189.

van Westen, R., Kliphuis, M. and Dijkstra, H.A. (2025a) ‘Collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in a strongly eddying ocean-only model’, Geophysical Research Letters, 52, e2024GL114532. doi: 10.1029/2024GL114532.

van Westen, R., Vanderborght, E., Kliphuis, M. and Dijkstra, H.A. (2025b) ‘Physics-based indicators for the onset of an AMOC collapse under climate change’, Journal Geophysical Research: Oceans, 130, e2025JC022651. doi: 10.1029/2025JC022651.

van Westen, R.M. and Baatsen, M. (2025) ‘European temperature extremes under different AMOC scenarios in the Community Earth System model’, Geophysical Research Letters, 52, e2025GL114611. doi: 10.1029/2025GL114611.

Vanderborght, E., Van Westen, R. and Dijkstra, H.A. (2025) ‘Feedback processes causing an AMOC collapse in the Community Earth System Model’, Journal of Climate, 38, pp. 5083–5102. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-24-0570.1.

Project summary

The TAOC project aims to determine the probability that the Atlantic Ocean circulation will collapse under climate change before the year 2100. A hierarchy of ocean-climate models will be used, to which we will apply modern rare event techniques.

Project partners

We collaborate with many other groups in other (H2020 and Horizon Europe) projects.

Project lead profile

Dr Henk Dijkstra secured a PhD in mathematics from the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) and is currently Professor of Dynamical Oceanography at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht (IMAU), Department of Physics, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Dijkstra holds a PIONIER award from the Dutch Science Foundation and a Lewis Fry Richardson Medal from the European Geosciences Union for his outstanding work in developing the nonlinear dynamical systems approach to oceanography and for his study of the role of ocean circulation in (palaeo)climate.

Project contacts

Dr Henk Dijkstra

Web: https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~dijks101/

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101005596).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: Overview of the Atlantic Ocean circulation, with surface currents indicated in red and deep currents in blue. The purple regions are deep convection sites where water is transformed. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is the zonally-integrated volume transport at every latitude and depth.

Figure 2: Tipping of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) in different climate models. The y-axis shows the northward volume transport of the AMOC at 26°N. Cyan lines denote the applied freshwater hosing (in million m³/s), which is gradually increased to correct for the salinity bias. Once the hosing reaches a critical value, the AMOC transport undergoes a rapid decline, indicating a tipping point.

Figure 3: Predicted (up to 2025) and projected (after 2025) surface buoyancy (heat/freshwater) flux from the atmosphere to the ocean. The curves show multi-model averages across a large ensemble of climate models. Under high- and intermediate-emission scenarios, the buoyancy input is projected to cross zero around 2055 and 2063, respectively, marking the onset of a tipping point (based on van Westen et al., 2025b).