Michael Magee

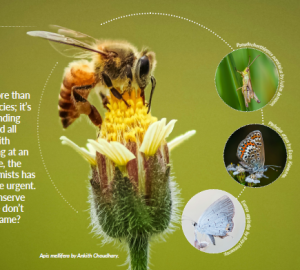

Taxonomy is more than just naming species; it’s about understanding the ties that bind all life on Earth. With species vanishing at an accelerating rate, the work of taxonomists has never been more urgent. How can we conserve something if we don’t even know its name?

It’s spring 2023 in Denmark. Thirty thousand schoolchildren aged 7 to 16 are prowling graveyards, playgrounds and roof gutters, collecting moss and lichen (bryophytes). Using identification keys, they map scientific names and coordinates. After wetting the sample, they place it under a microscope. Little bulbous bodies, a millimetre or two long, begin to emerge. Tiny feet with hooked toes claw their way out from the deep green silhouettes. Waking up from their sleep are water bears, or tardigrades. Seven thousand samples containing tardigrades are sent to the Natural History Museum of Denmark, where taxonomist Piotr Gąsiorek eagerly waits to identify the species. This nationwide citizen science effort helped map Denmark’s bryophytes, more than quadrupled the number of known tardigrade species in the country and discovered ten species new to science. The children will help Piotr name their discovered species.

This scene captures the spirit of TETTRIs, a €6 million Horizon Europe project now in its final stretch. Coordinated by the Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities (CETAF), with 17 partners in 11 countries, TETTRIs is working to tackle a problem that many people don’t realise exists: a shortage of taxonomists and the knock-on effects this has on everything from food and medicine security to consumer supply chains and conservation policy. The project’s mission is as ambitious as it is urgent—to overhaul Europe’s taxonomic capacity by modernising tools, establishing training programmes and creating collaborations to strengthen a field that underpins all of biodiversity science.

The hidden crisis beneath the biodiversity emergency

Most people who care about nature are aware of the biodiversity crisis: the accelerating loss of species and ecosystems worldwide, akin to a mass extinction event. But far fewer realise that we are losing our capacity to even identify and describe species. Taxonomy—the work of naming, describing and classifying life—has been slowly hollowed out over decades. Many expert taxonomists have retired or left the field.

Fewer students are trained in classical taxonomy, and funding for foundational descriptive work has dwindled. As a result, even in well-studied Europe, many groups of organisms are poorly known or not known at all, especially small, cryptic or soil-dwelling creatures that are essential for ecosystem functioning, like our tardigrades.

The consequences are profound. If a species is not described, it is effectively invisible to science, conservation law and environmental monitoring. A butterfly can’t be listed as endangered if it has no name. An invasive snail can’t be controlled if nobody can tell it apart from its harmless relatives. Even cutting-edge conservation tools like environmental DNA sampling or AI-based image recognition depend on robust reference datasets of correctly identified species, which only taxonomists can provide.

This is where TETTRIs steps in. The multifaceted and interdisciplinary project exists to highlight taxonomy as a critical infrastructure for biodiversity science, akin to the roads and bridges that support an economy. Over 42 months (December 2022 to May 2026), TETTRIs has been building new bridges between amateur and professional taxonomists, field ecologists, molecular biologists, citizen scientists, policymakers and the public. The goal is nothing less than a cultural shift: to make taxonomy visible, connected, and to support the next generation of taxonomists.

A celebration of naming: Taxonomy Recognition Day

One of TETTRIs’ most visible aspects has been Taxonomy Recognition Day (TRD), held each year on 23 May. The date was chosen as it marks the birthday of the ‘Godfather of Taxonomy’, Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish naturalist who gave us the binomial naming system still used today. Genus Homo followed by species sapiens. People are invited to share a picture of their favourite plant or animal on social media, along with its scientific name. The hashtag #NameItToSaveIt allows the campaign’s reach to be measured.

The impact has been striking. In its second edition in 2025, TRD reached over 700 000 people across social media and brought together institutions on five continents. It has become an annual rallying point for the taxonomic community—a chance to step out of the lab and show the world why their work matters. For a field often perceived as old-fashioned or dusty, TRD has injected a welcome shot of energy and visibility.

Community-based approach: the 12 satellite projects

A unique funding system was tested in TETTRIs, asking external projects to validate tools and methods developed during the project’s first year. Twelve ‘satellite’ projects were selected from dozens of applications. These projects cover everything from molecular barcoding of alpine spiders to citizen-science surveys of animal footprints in the snow, from AI-based snail recognition to national pollinator reference collections.

Table 1: TETTRIs’ 12 satellite projects. Read more about the projects: https://tettris.eu/awarded-projects/

| Project | Lead country | Focus |

| FOOTPRINTS-CITSCI | Norway | Citizen science + image recognition to map animal tracks |

| SoilMATs | Italy | Training new experts on soil meiofauna |

| NEXTRAD | Macaronesia archipeligo | Advancing Macaronesian Lotus (Leguminosae) species diversity |

| CRYPTERS | Italy | Molecular markers to reveal cryptic alpine spiders |

| TEOSS | Spain, Italy, Greece | AI sound recognition of grasshoppers |

| TrAILSID | Germany | AI image ID of European land snails |

| iSedge | Spain | Digital platform for sedge taxonomy |

| INC-STEP | Spain | Building national pollinator reference collections |

| ARCADE | Portugal | Strengthening Portuguese pollinator reference collections |

| Balkan PolliS | Serbia | Documenting Balkan wild bees and hoverflies |

| TNLS | Belgium | Linking taxonomic names across datasets |

| L.U.C.E. | Italy | Filling knowledge gaps on Europe’s fireflies |

They are deliberately diverse because taxonomy itself is multifaceted. These projects are due to end in October 2025, after which we will assess what worked particularly well. The aim is to identify what works and then plan to scale up promising approaches across Europe.

The bigger picture

Every piece of food we eat has a species name. A significant portion of our medicine is derived from nature. Most of the oxygen in the air we breathe was produced by marine microorganisms. We are nature, and nature is us. Our economy is heavily dependent on natural resources, with 75% of the European economy relying on ecosystem services. Be it building material, clothing fabrics or flood protection. The problem with accelerated biodiversity loss is recognised globally.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) sets global targets—now framed in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—to halt and reverse biodiversity loss. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) provides the scientific assessments that guide these targets, while the Biodiversity Strategy 2030 and EU Nature Restoration Law turn them into binding commitments at a regional level by requiring countries to restore degraded ecosystems. Achieving any of these goals depends on taxonomy: without knowing which species exist, where they are, and how they are changing, it is impossible to track biodiversity loss, measure restoration success or design effective conservation policy.

Results so far

The TETTRIs project has so far advocated open access to digital reference collections of European pollinators. These are museum archives that allow accurate identification of species in the field. A new portal has been launched to help people find taxonomic experts in Europe as well as taxonomic services. New training frameworks for the next generation have been produced and validated. TETTRIs has advanced knowledge of modern tools such as DNA barcoding and AI-powered species ID through image and sound recognition. These tools allow for speedy assessment of biodiversity. Citizen participation has been another focus. Innovative approaches to engaging the public in biodiversity observation have been tested. Citizen involvement is vital for building support for protective legislation. When people can notice and document the positive changes brought by measures such as the EU Nature Restoration Law, their support for conservation grows stronger. By the end of the project (May 2026), a legacy blueprint for transforming taxonomy in Europe will be available.

Looking forward

As TETTRIs enters its final few months, attention is turning to legacy. Partners are drafting policy briefs aimed at embedding taxonomy in EU biodiversity strategies. Protocols from the satellite projects on AI tools, training, molecular workflows and data standards are being compiled into open resources. The team is already planning a continuation to build upon success and scale up validated approaches.

Most of all, the project has shown that taxonomy can be re-energised if it is given the resources, visibility and support it needs. By teaching, equipping and connecting taxonomists—and by showing the public the importance of naming life—TETTRIs is proving that even the hardy tardigrades matter, because each is a thread in the interconnected fabric of our living world. Understanding the threads is the cornerstone for solving today’s environmental crises.

And so, as classrooms in Denmark decide on the names of our new species, it is hard not to feel hopeful. These names are more than labels. They are acts of recognition, a way of communicating in a global scientific language, the first step toward protection. TETTRIs has made it its mission to ensure those acts continue—so that we, and future generations, can enjoy endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.

Project summary

Taxonomy is the science of naming, describing and classifying life. It is vital in tackling biodiversity loss. TETTRIs strengthens Europe’s capacity by training new experts, developing innovative tools, and engaging communities. The project supports the EU Nature Restoration Law and global biodiversity targets, ensuring we know what species exist, where they are and the connections that bind life on Earth.

Project partners

See: https://tettris.eu/consortium-partners

Project lead profile

With over 5000 scientists in 27 countries, CETAF is Europe’s network of biological and geological collections. The consortium is a leading European voice for taxonomy and systematic biology. With a secretariat based in Brussels, CETAF actively influence policy for the benefit of biodiversity in Europe.

Project contacts

Marta Leon Monedero, Project Manager

Email: marta.leon@cetaf.org

Michael Magee, Communications Manager

Email: magee@snm.ku.dk

Web: tettris.eu/

Bluesky: bsky.app/profile/tettris.bsky.social

X: @TETTRIsEU

Facebook: @TETTRIsEU

Instagram: @TETTRIsEU

LinkedIn: /company/tettris

Funding

This project has been funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101081903).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

TETTRIs consortium partners.