The paradox of connection

In an increasingly digitised world, people can connect to almost anyone at almost any time. Yet loneliness, aggression and stress are rising.

The paradox is striking: as we grow more connected online, we become more out of touch—literally.

Our fingertips glide over glass screens, and we like posts. But human skin, our largest sensory organ, rarely meets another’s. The squeeze of reassurance, the comfort of a hug—these gestures diminish in daily life. As digital communication expands, physical connection contracts, potentially carrying unforeseen psychological costs.

That concern lies at the heart of TOUCHNET (Touch-Induced Brain Network Signatures for Social Processing and Stress Reduction), a five-year project funded by the European Research Council. The project aims to understand how touch shapes our social bonds and helps us cope with stress. By combining large-scale real-world data with cutting-edge brain imaging, TOUCHNET will build the first comprehensive picture of how interpersonal touch shapes social connection—from behaviour to neural signatures.

The missing sense

Humans are social animals, and touch is a mode of emotional communication. Parents soothe infants by stroking them, lovers express affection through caresses, and friends offer comfort with a pat on the shoulder. Yet compared to vision or hearing, touch has been a fairly neglected sense in science and society alike.

In the 1950s, psychologist Harry Harlow demonstrated its importance with a controversial experiment: baby rhesus monkeys preferred a soft cloth ‘mother’ to a wire one that provided milk. Comfort outweighed nourishment (Harlow, 1958).

Since then, studies have confirmed that touch calms the nervous system, lowers heart rate, and strengthens social bonds (Schirmer, Croy and Ackerley, 2023). Lack of touch, conversely, relates to loneliness, anxiety and poorer health (Packheiser et al., 2024). But most evidence comes from laboratories, not everyday life.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many experienced ‘touch hunger’, the deprivation of physical contact. Surveys linked touch deprivation to higher stress and lower well-being—yet these relied mostly on questionnaires, not real-time data. The field still lacks robust, ecological evidence of how, when and why people touch, and how those moments shape body and brain.

Inside the science of affective touch

Touch is not a single sense but a symphony of signals. For decades, scientists thought tactile sensations were transmitted only by fast A-beta fibres detecting pressure and texture. But in the 1990s, researchers discovered a second, slower system in humans, designed specifically for social touch: C-low threshold mechanoreceptors, or C-LTMRs (Vallbo, Olausson and Wessberg, 1999).

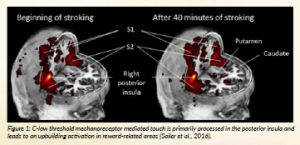

These unmyelinated nerve fibres, concentrated in hairy skin, respond best to gentle stroking at around three centimetres per second—the same speed people naturally use when caressing their partner, child or friends (Bytomski et al., 2020). Signals from C-LTMRs travel to the posterior insula, a brain region that monitors internal bodily states, and then to the superior temporal gyrus (STG), an area associated with social perception (Davidovic et al., 2016).

This pathway connects physical contact to emotional experience. Stimulating it produces calm, pleasure and reward—the hallmarks of affective touch. In one of the experiments, for instance, slow stroking activated reward-related brain areas and enhanced coupling between the insula and social brain networks (Sailer et al., 2016). Animal studies in mice even suggest a causal role of these fibres in social interactions (Huzard et al., 2022).

Touch also interacts with allostasis—the brain’s predictive regulation of the body. Affective touch can lower arousal and promote parasympathetic activity, buffering stress. Even newborns benefit: gentle stroking reduces pain and heart rate (Fairhurst et al., 2014; Püschel et al., 2022), and infants who experience more touch show stronger brain connectivity in empathy-related regions (Brauer et al., 2016). Touch thus both regulates stress and helps build the neural foundation for social behaviour.

What we still don’t know

Despite progress, key questions remain. How often do people touch each other in daily life? Who initiates it, and in what contexts? Does touch truly reduce stress outside the lab—at home, at work or on public transport? And do culture, personality and context alter how touch is experienced?

Existing data are fragmentary. Some studies show that women are touched more than men, younger people more than older ones, and that touch is more public in southern than northern Europe (Gallace and Spence, 2010). However, sample sizes are small.

One of the most thorough naturalistic studies was published in 1985, when researchers observed 39 people over several days and catalogued 800 touch events (Jones and Yarbrough, 1985): 74% served a social purpose—comfort, support, affection. But today’s world is radically different, with new norms shaped by digital life.

More recently, a cross-cultural survey of 15 000 people across 42 countries found that touch remains integral to family and friendship bonds worldwide (Sorokowska et al., 2021). Yet even this study only asked whether participants had touched someone in the past week, not how often or with what emotional effect.

Ilona Croy, Professor of Clinical Psychology and project lead of TOUCHNET, explains: “We needed a way to capture touch as it happens—in context, with emotion and physiology attached. That’s what TOUCHNET will do.”

The TOUCHNET vision

TOUCHNET seeks to organise what Croy calls the ‘patchwork’ of touch research.

Funded by the European Research Council, the five-year programme bridges psychology, neuroscience and data science through two main objectives.

- Build the world’s largest ecological database of interpersonal touch—a map of how, when and why people touch, and how these events affect stress and emotion.

- Identify the neural mechanisms linking touch to social connection and stress reduction—the brain’s ‘signatures’ of touch.

Together, these efforts will unite the social and the neural world, creating a framework for understanding human connection in real-world settings.

Work Package 1 – Mapping touch in real life

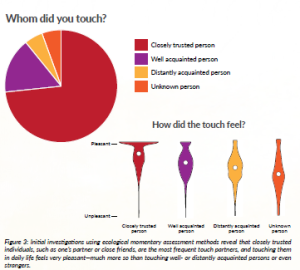

The first phase focuses on the ecology of touch. To move beyond self-reports, the team will use ecological momentary assessment (EMA), prompting participants via smartphone apps or wearables to record touch events as they happen.

In the initial study, hundreds of participants across at least ten centres will log every instance of touch over several days. Based on pilot work, this endeavour is expected to yield more than 100 000 touch moments in total. Each record will include who touched whom, in what context and how it made participants feel, along with their stress levels. This will be enriched with individual sociodemographic, well-being and personality data.

A second study will combine EMA with physiological monitoring of heart rate to see whether natural touch events produce measurable drops in stress. A third will explore the giving side of touch: why people reach out physically and how that action affects their well-being.

If successful, TOUCHNET’s real-world database will become a public resource for researchers worldwide, offering unprecedented insight into the rhythms of human contact.

Work Package 2 – The touch of the brain

The second phase moves to the lab, examining how touch reshapes neural networks. The central hypothesis: affective touch activates two overlapping systems—the social brain network, which processes interpersonal cues and the allostatic–interoceptive network, which regulates internal states like stress and calm. These networks share key hubs—the insula, anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala—linking sensations from skin to emotion and social behaviour.

In one study, participants will undergo MRI scans during controlled touch versus no-touch conditions while engaging in social tasks, such as viewing friendly faces or experiencing mild exclusion. Researchers will examine how touch alters connectivity within and between the two networks. A second study using ultra-high-field 7-Tesla MRI will focus on micro-level activity, revealing how tactile signals propagate through cortical layers.

A third experiment will test interpersonal synchrony—the alignment of heart rate, brain activity and movement during interaction. Using fNIRS hyperscanning, pairs of participants will engage in semi-natural conversations with and without touch to see whether it enhances neural ‘tuning’ between their brains.

Together, these studies aim to show how touch modulates the brain’s social and regulatory circuits and how it may literally bring minds into sync.

Why it matters

Why devote years and millions of euros to studying touch? Because, as Croy argues, touch may be the most fundamental—and most endangered—channel of human connection.

Modern life is filled with touch substitutes: emojis, virtual hugs, vibrating phone alerts and even haptic gloves for virtual reality. Yet none of these replicate the complex, bi-directional feedback of skin-to-skin contact. Understanding the biology of touch could help design better digital communication tools—ones that convey warmth and empathy, not just information.

There are also profound implications for mental health. People with autism spectrum conditions often show altered responses to gentle stroking, hinting at disruptions in the C-LTMR system. Those who experience little or no touch—through social isolation, trauma or illness—are at higher risk of anxiety and depression. If researchers can identify the neural pathways that make touch soothing or rewarding, they may be able to develop targeted therapies that simulate or enhance those effects.

At a societal level, TOUCHNET’s data could inform public health strategies to promote well-being through touch in hospitals, elder care, schools and workplaces. Even small interventions, like encouraging physical play between parents and children or safe touch in healthcare settings, might yield measurable benefits.

As Croy notes: “We are not trying to romanticise touch. We’re trying to understand it so that we can use it wisely in a world where it’s becoming rare.”

References

Brauer, J., Xiao, Y., Poulain, T., Friederici, A.D. and Schirmer, A. (2016) ‘Frequency of maternal touch predicts resting activity and connectivity of the developing social brain’, Cerebral Cortex, 26(8), pp. 3544–3552. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw137.

Bytomski, A., Ritschel, G., Bierling, A., Bendas, J., Weidner, K. and Croy, I. (2020) ‘Maternal stroking is a fine-tuned mechanism relating to C-tactile afferent activation: an exploratory study’, Psychology & Neuroscience, 13(2), pp. 149–157. doi: 10.1037/pne0000184.

Davidovic, M., Jönsson, E.H., Olausson, H. and Björnsdotter, M. (2016) ‘Posterior superior temporal sulcus responses predict perceived pleasantness of skin stroking’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 432. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00432.

Fairhurst, M.T., Löken, L. and Grossmann, T. (2014) ‘Physiological and behavioral responses reveal 9-month-old infants’ sensitivity to pleasant touch’, Psychological Science, 25(5), pp. 1124–1131. doi: 10.1177/0956797614527114.

Gallace, A. and Spence, C. (2010) ‘The science of interpersonal touch: an overview’, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(2), pp. 246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.004.

Harlow, H.F. (1958) ‘The nature of love’, American Psychologist, 13(Gallace and Spence, 2010), pp. 673–685. doi: 10.1037/h0047884.

Huzard, D., Martin, M., Maingret, F., Chemin, J., Jeanneteau, F., Mery, P.F., Fossat, P., Bourinet, E. and François, A. (2022) ‘The impact of C-tactile low-threshold mechanoreceptors on affective touch and social interactions in mice’, Science Advances, 8(26), eabo7566. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo7566.

Jones, S.E. and Yarbrough, A.E. (1985) ‘A naturalistic study of the meanings of touch’, Communication Monographs, 52(1), pp. 19–56. doi: 10.1080/03637758509376094.

Packheiser, J., Hartmann, H., Fredriksen, K., Gazzola, V., Keysers, C. and Michon, F. (2024) ‘A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions’, Nature Human Behaviour, 8(6), pp. 1088–1107. doi: 10.1038/s41562-024-01841-8.

Püschel, I., Reichert, J., Friedrich, Y., Bergander, J., Weidner, K. and Croy,

- (2022) ‘Gentle as a mother’s touch: C-tactile touch promotes autonomic regulation in preterm infants’, Physiology & Behavior, 257, 113991. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113991.

Sailer, U., Triscoli, C., Häggblad, G., Hamilton, P., Olausson, H. and Croy,I. (2016) ‘Temporal dynamics of brain activation during 40 minutes of pleasant touch’, NeuroImage, 139, pp. 360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.031.

Schirmer, A., Croy, I. and Ackerley, R. (2023) ‘What are C-tactile afferents and how do they relate to “affective touch”?’, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 151, 105236. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105236.

Sorokowska, A., Saluja, S., Sorokowski, P., Frąckowiak, T., Karwowski, M., Aavik, T.,… & Croy, I. (2021). Affective interpersonal touch in close relationships: A cross-cultural perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(12), 1705-1721. doi: 10.1177/0146167220988373.

Vallbo, Å.B., Olausson, H. and Wessberg, J. (1999) ‘Unmyelinated afferents constitute a second system coding tactile stimuli of the human hairy skin’, Journal of Neurophysiology, 81(6), pp. 2753–2763. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2753.

Project summary

Human communication is becoming increasingly digitised, with potential adverse effects on social interaction and well-being. TOUCHNET investigates how interpersonal touch fosters social connection and regulates stress. Combining real-world data collection and wearable sensors, the project will map how, when and why people touch. Utilising advanced brain imaging, it will further identify the neural signatures of affective touch within social and allostatic brain networks. In doing so, TOUCHNET seeks to uncover the mechanisms by which touch reduces stress and promotes social inclusion, as well as the contextual and moderating factors that shape these effects, ultimately guiding more compassionate forms of communication.

Project lead profile

Ilona Croy is Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Jena, Germany. Trained in Dresden and Sweden, she specialises in sensory-social neuroscience, focusing on affective touch and olfaction in relation to emotion, stress and mental health. Her interdisciplinary work integrates neuroscience and clinical psychology to understand how sensory processes shape well-being and social connection.

Project contacts

Ilona Croy

Email: ilona.croy@uni-jena.de

Web: www.uni-jena.de/en/288508/touch-me

Web: www.klipsy.uni-jena.de/

Book: https://www.komplett-media.com/products/touch-me?srsltid=AfmBOopa9rclBgLm2svgsbHKkCaiV2yLRnH4PFQsv8_n8F5Q7NUetAcP

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101170227).

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Figure legends

Figure 1: C-low threshold mechanoreceptor mediated touch is primarily processed in the posterior insula and leads to an upbuilding activation in reward-related areas (Sailer et al., 2016).

Figure 2: fNIRS hyperscanning allows the identification of how touch enhances neural synchrony between individuals.

Figure 3: Initial investigations using ecological momentary assessment methods reveal that closely trusted individuals, such as one’s partner or close friends, are the most frequent touch partners, and touching them in daily life feels very pleasant—much more so than touching well- or distantly acquainted persons or even strangers.